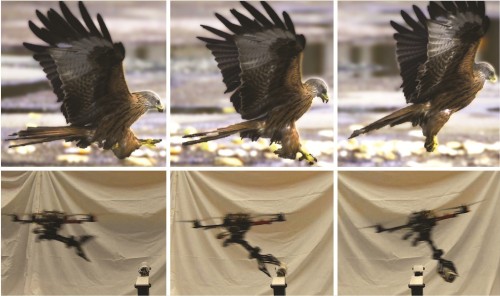

A red kite and a drone swoop down on their prey. (Courtesy: Vijay Kumar)

By Hamish Johnston

A bird of prey swoops out of the sky, grabs its victim from the ground and flies off into the distance. It’s what a bird does instinctively, but how could we get a drone aircraft to do the same thing? That’s the subject of one of the papers in a special issue of the journal Bioinspiration & Biomimetics that focuses on “Bioinspired flight control”.

The above sequence of images is from a paper entitled “Toward autonomous avian-inspired grasping for micro aerial vehicles” by Vijay Kumar and colleagues at the University of Pennsylvania. The special issue also includes work on aircraft inspired by flying snakes, flocking birds and incredibly stable moths.

Staying on the theme of inspiration, in 1714 the British government offered a prize of £10,000 (more than £1 million in today’s money) to anyone who devised a way of determining longitude at sea – something that was crucial for efficient navigation of the open oceans.

Now 300 years later, the UK-based charity Nesta has revived the Longitude Prize with the aim of finding a solution to a major challenge facing society. The new prize is worth £10 million and on Monday Nesta announced that the first step in the competition will be to decide which problem to solve. A committee comprising 18 scientists, business people and journalists has come up with a shortlist of six pressing problems ranging from finding a cure for paralysis to building environmentally friendly commercial aircraft.

Not surprisingly, the response in the science blogosphere has been mixed. Alice Bell, for example, asked “What sort of dystopian austerity logic asks the public to vote on whether they want to fund research on water or food security?”. Her blog entry is called “The Longitude Prize: Science’s Hunger Games“.

Meanwhile over on the Guardian’s Occam’s Corner blog the physicist and Longitude committee member Athene Donald argues against the view that the prize is “merely a scientific version of Britain’s Got Talent”. The comparison to the popular television programme was actually made by the British Prime Minister David Cameron, who is also an ardent supporter of the prize.

There is a good round-up of arguments for and against the prize in “Should we give the Longitude Prize some latitude?” by the biologist Stephen Curry. And if you think the prize is a good idea, what about a similar contest for physics – what would be on your shortlist of problems to be solved?

Those of you who were around in the 1970s know that there was some speculation then that the Earth’s climate might be cooling – with some tabloids predicting a new ice age. In 1975 Physics World’s North America correspondent Peter Gwynne wrote a much more sober assessment of the science at the time for Newsweek magazine. The article (PDF), which is still widely quoted today, suggested that agricultural productivity in England had already been reduced by this cooling trend.

This week Gwynne revisits that article in “My 1975 ‘Cooling World’ story doesn’t make today’s climate scientists wrong” and explains – with help from experts Michael Mann and Gavin Schmidt – how climate science has improved since he wrote his article 39 years ago.

On Tuesday the Harvard Gazette published a fascinating interview with the Canadian particle physicist Melissa Franklin. Before embarking on a career in science that would eventually lead to a Harvard professorship, Franklin quit traditional schooling at the age of 13 and helped start a “free school”, where she made a short film that was nominated for an Academy Award. Then at the age of 15 she decamped to London where she decided to study physics and struggled to pass her A-level exams. Her poor grades make it unlikely that she would be admitted to the University of Toronto to do physics, so she spent a month talking to everyone she could in the physics department and eventually convinced them to let her in. The interview is entitled “Physics was paradise”, and I’m sure it still is for Franklin.

Guidelines

Show/hide formatting guidelines

this text was deletedwhere people live in harmony with nature and animals</q>

Some text