Tag archives: exoplanets

Kepler – it’s not all doom and gloom just yet

By Tushna Commissariat

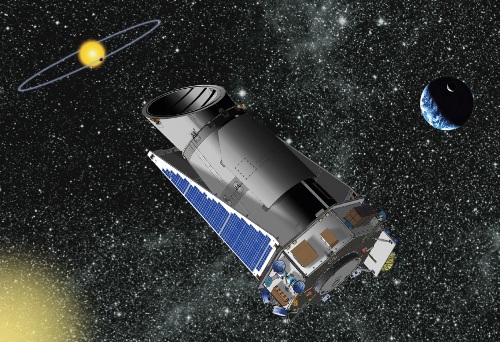

NASA’s Kepler space telescope. (Courtesy: NASA)

To much general dismay, earlier this month NASA officials announced that their Kepler space telescope had gone into a self-imposed “safe mode”, something that the telescope is programmed to do if one of its primary systems is not fully functional. Although the telescope was then rebooted, it shut down again this week and it seems that all is definitely not well with our favourite exoplanet spotter: the mission collaboration announced that the instrument has suffered a critical failure and may never be fully operational again.

View all posts by this author | View this author's profile

Of mice and ‘little green men’

By Tushna Commissariat

Just called to say hello?

(Wikimedia Commons/Crobard)

There’s nothing quite like mentioning extraterrestrials or aliens to get us “Earthlings” all excited or riled up! Late last week, a paper popped up on arXiv, by astronomer Alan Penny from the University of St Andrews. He outlines an incident where, for a short while, the possibility of alien contact was seriously considered. He was talking about what was ultimately the discovery of the first pulsar; but at the time the researchers couldn’t help but wonder if they had come across the first “artificial signal” from outer space.

The exciting happenings began in August 1967, when Jocelyn Bell Burnell (then a graduate student working with Antony Hewish – controversially, only Hewish won the Nobel prize for the pulsar discovery in 1974) at the University of Cambridge, noticed a particular source that had a “flickering pattern” that, over a few weeks, she realized showed up regularly each day at the same sidereal time. That December Bell pinpointed the specific position of the source in the sky using another telescope and the discovery was confirmed. In the coming months, three more similar patterns were found and the researchers agreed on “pulsating stars” or pulsars being the source. But during those winter months, the possibility that they had encountered the first alien signal loomed large. In fact, Brunell and colleagues dubbed the first pulsar LGM-1 or “Little Green Men”; although it was changed to CP 1919, and is now known as PSR B1919+21.

View all posts by this author | View this author's profile

Hubble – one million and going strong

By Tushna Commissariat

I have already raved on about the awesomeness of the Hubble Space Telescope in my blog entry about its 21st anniversary in April this year. Now, the telescope has crossed yet another milestone – on Monday 4 July the Earth-orbiting observatory logged its one-millionth science observation! The image above is a composite of all the various celestial objects ranging through stars, clusters, galaxies, nebulae, planets, etc that Hubble has catalogued over the years. Click on the image for a hi-res version. [Credit: NASA, ESA and R Thompson (CSC/STScI)]

The telescope has had a significant impact on all fields of science from planetary science to cosmology and has provided generations with breathtaking images of our universe ever since it was launched on 24 April 1990 aboard Discovery’s STS-31 mission.

Hubble’s counter reading includes every observation of astronomical targets since its launch. The millionth observation made by Hubble was during a search for water in the atmosphere of an exoplanet almost 1000 light-years away from us. The telescope had trained its Wide Field Camera 3, a visible and infrared light imager with an on-board spectrometer on the planet HAT-P-7b, a gas giant planet larger than Jupiter orbiting a star hotter than our Sun. HAT-P-7b has also been studied by NASA’s Kepler telescope after it was discovered by ground-based observations. Hubble now is being used to analyse the chemical composition of the planet’s atmosphere.

“For 21 years Hubble has been the premier space-science observatory, astounding us with deeply beautiful imagery and enabling ground-breaking science across a wide spectrum of astronomical disciplines,” said NASA administrator Charles Bolden. He piloted the space shuttle mission that carried Hubble to orbit. “The fact that Hubble met this milestone while studying a far away planet is a remarkable reminder of its strength and legacy.”

Hubble has now collected more than 50 terabytes – the archive of that data is available to scientists and the public at http://hla.stsci.edu/

And take a look at this Physics World article by astrophysicist Mark Voit where he looks at the most iconic images Hubble has produced over the years – Hubble’s greatest hits

The NASA video below was created last year for the 20th Hubble anniversary celebration and tells you how you could send a message to Hubble that will be stored in its archive.

View all posts by this author | View this author's profile

Plants like we have never seen them before

Gliese 667 is one of two multiple star systems known to host planets below 10 Earth masses. (Courtesy: ESO/L Calçada)

By Tushna Commissariat

If you have thought about planets with two or more suns ever since you saw the dual suns of Tatooine in the first Star Wars film, looks like you are on the same wavelength as some astrobiologists. Jack O’Malley-James, a PhD student at the University of St Andrews, Scotland, has been studying what kind of habitats would exist on Earth-like planets orbiting binary or multiple star systems. He shared his results with peers at the RAS National Astronomy Meeting in Llandudno, Wales on Tuesday 19th April.

O’Malley-James and his team have been running simulations for planets that would orbit multiple star systems and trying to understand the kind of vegetation that might flourish there, depending on the type of stars in the system. Energy via photosynthesis is the foundation for majority of life on Earth, and so it is natural to look for the possibility of photosynthetic processes occurring elsewhere.

With different types of stars occurring in the same system, there would be different spectral sources of light shining on the same planet. Because of this plants may evolve that photosynthesize all types of light, or different plants may choose specific spectral types. The latter would seem more plausible for plants exposed to one particular star for long periods, say the researchers.

Their simulations suggest that planets in multi-star systems may host exotic forms of the plants we see on Earth. “Plants with dim red dwarf suns for example, may appear black to our eyes, absorbing across the entire visible wavelength range in order to use as much of the available light as possible,” says O’Malley-James. He also believes the plants may be able to use infrared or ultraviolet radiation to drive photosynthesis.

The team simulated combinations of G-type stars (yellow stars like our Sun) and M-type stars (red-dwarf stars), with a planet identical to Earth, in a stable orbit around the system, within its habitable “Goldilocks zone”. This was because Sun-like stars are known to host exoplanets and red dwarfs are the most common type of star in our galaxy, often found in multi-star systems, and are old and stable enough for life to have evolved.

While the binary systems were not exact copies of any particular observed systems, plenty of M-G star binary systems exist within our own galaxy. O’Malley-James calculated the maximum amount of light per unit area- referred to as the “peak photon flux density” from each of the stars as seen on the planets for each set of simulations. This was compared to the peak photon flux density on Earth to determine whether Earth-like photosynthesis would occur.

Factors like star separation were taken into consideration, to give the best possible scenario for photosynthesis. “We kept the stars as close to the planet as we could, so that there would be a useful photon flux from each one [star] on the planet’s surface while still maintaining a stable planetary orbit and a habitable surface temperature,” says O’Malley James.