Tag archives: out and about

A virtual tour of virtual reality

By Margaret Harris at Photonics West in San Francisco

“How many people in this room are wearing smart glasses today?”

When Bernard Kress, a photonics expert and optical architect on Microsoft’s HoloLens smart-glasses project, posed this question at the Photonics West trade show, he had reason to expect a decent response. He was, after all, speaking at a standing-room-only session on virtual reality, augmented reality and mixed reality (VR, AR and MR), and the audience was packed with tech-friendly, early-adopter types who had come specifically because they’re interested in such devices. Surely, someone in the audience would put up their hand.

View all posts by this author | View this author's profile

Grabbing a slice of the pie in the sky

(Courtesy: NASA)

By Margaret Harris at the European Planetary Science Congress in Riga, Latvia

If you wanted to mine an asteroid, what would you need? Right now, it’s a hypothetical question: only a handful of spacecraft have ever visited an asteroid, and fewer still have studied one in detail. As commercial ventures go, it’s not exactly a sure thing. But put that aside for a moment. If you wanted to create an asteroid-mining industry from scratch, how would you do it?

Well, for starters, you’d need to know which asteroids to target. “Not every mountain is a gold mine, and that’s true for asteroids too,” astrophysicist Martin Elvis told audience members at the European Planetary Science Congress (EPSC) yesterday. For every platinum-rich asteroid sending dollar signs into investors’ eyes, Elvis explained there are perhaps 100 commercially useless chunks of carbon whizzing around out there, and the odds for water-rich asteroids aren’t much better. Moreover, some of those valuable asteroids will be impractical to mine, either because of their speed and location or because they’re too small to give a good return on investment. “Smaller asteroids aren’t even worth a billion dollars,” Elvis scoffed. “Who’d get out of bed for that?”

View all posts by this author | View this author's profile

A temporary lack of neutrons

The guide hall at the HANARO research reactor in Daejeon, Republic of Korea.

By Margaret Harris in Daejeon, Republic of Korea

For almost three years, the HANARO research reactor has been idle. Built in 1995 as a hub for neutron-scattering experiments, radioisotope production and other scientific work, HANARO (High Flux Advanced Neutron Application Reactor) is the only facility of its kind in the Republic of Korea, and it underwent a major upgrade in 2009. Then, in 2014, the facility became a delayed casualty of the meltdown at Japan’s Fukushima Dai-Ichi nuclear power station, as enhanced regulatory scrutiny led to the discovery that the reactor hall’s outer wall was not up to the latest standards. An enforced shutdown followed while the wall was reinforced, and although the works were supposed to take just 18 months, opposition from local citizens’ groups has led to further delays.

View all posts by this author | View this author's profile

A spotlight on accelerators in industry – sort of

Robert Kephart of Fermilab speaking about the “beam business” at IPAC17.

By Margaret Harris at the International Particle Accelerator Conference in Copenhagen

Normally, you’d expect a particle-accelerator conference to focus on research – either the fundamental research done at accelerator facilities around the world, or the applied research required to get such facilities up and running in the first place. And for the most part, that has been absolutely true of the 8th International Particle Accelerator Conference (IPAC), which is taking place this week on the outskirts of Copenhagen, Denmark.

On Tuesday, however, the conference organizers dedicated a session to the ways that accelerator science engages with industry. In a two-hour series of talks, audience members heard from speakers as varied as Bjerne Clausen, CEO of the Danish chemical technologies firm Haldor Topsoe; Bob Kephart, director of the Fermilab-affiliated Illinois Accelerator Research Center (IARC); and Giovanni Anelli, who leads the Knowledge Transfer group at CERN.

View all posts by this author | View this author's profile

US immigration and trade policies provoke debate at Photonics West

San Francisco’s Golden Gate Bridge welcomes scientific visitors to Photonics West – except for those banned from travelling to the US.

By Margaret Harris at Photonics West in San Francisco

“I’m an immigrant. I stole one American job. I helped create hundreds of thousands of others.”

Deepak Kamra’s words caused a stir among listeners at Photonics West, the massive industry trade show and scientific conference that descends on San Francisco, California each winter. Speaking at a panel discussion on “Brexit, US Policy, EU and China,” the Delhi-born veteran of the Silicon Valley venture capital scene said that he expected the new US administration – which recently imposed a travel ban on visitors from seven majority-Muslim countries – to target Asian and South Asian technology workers next. Restrictions on the number of foreign-born students studying science, technology, engineering or mathematics (STEM) at US universities could follow. Ultimately, Kamra concluded, “We are going to lose a lot of qualified people.”

View all posts by this author | View this author's profile

Open science, accessible science?

Preparing to navigate the exhibit hall at the European Science Open Forum on crutches

By Margaret Harris

As I prepared to travel to Manchester earlier this week for the 2016 European Science Open Forum (ESOF), I had an unwanted extra item on my to-do list: working out, in detail, whether it was physically possible for me to attend.

My problem was my foot: a few weeks ago, I broke it, and as ESOF approached, it became clear that my injury wouldn’t heal in time. I was wary of trying to do a conference on crutches, but the reassuring responses to my queries (yes, my hotel had accessible rooms; yes, the venue for the conference, Manchester Central, was “very accessible”) convinced me that it would be okay. So I headed off to Manchester last Sunday for two days of science talks – and got an eye-opening lesson on what it’s like to attend a scientific conference with a physical disability.

Playing poker with robots on Mars

A prototype of the ExoMars rover trundles around inside the “space dome” at the Cheltenham Science Festival.

By Margaret Harris

How do you keep an astronaut alive, sane and (ideally) happy during a mission to Mars? The world’s space agencies would very much like to know the answer, but gathering data is tricky. The International Space Station (ISS) makes a good testbed for experiments on the physical effects of space travel, but psychologically speaking, ISS astronauts enjoy a huge advantage over their possible Mars-bound counterparts: if something goes badly wrong on the station, home is just a short Soyuz ride away. Martian astronauts, in contrast, will be on their own.

For this reason, space agencies have become interested in learning how people cope in extreme environments here on Earth, particularly in locations where rescue is not immediately possible. That’s why the European Space Agency (ESA) sent Beth Healey, a British medical doctor, to spend the winter of 2015 at Concordia Research Station, a remote base in the interior of Antarctica. During the continent’s nine-month-long winter, temperatures at Concordia can plunge as low as –80 °C, making it inaccessible even to aeroplanes, which cannot operate at temperatures below –50 °C. So once the last flight left in February 2015, Healey and the 12 other members of the overwintering team were stuck there until November.

View all posts by this author | View this author's profile

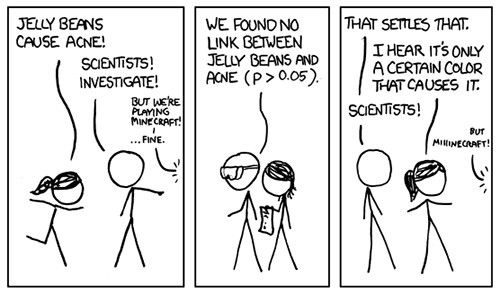

On the frontline of the ‘reproducibility crisis’

By Margaret Harris

The “reproducibility crisis” in science has become big news lately, with more and more seemingly trustworthy findings proving difficult or impossible to reproduce. Indeed, a recent Nature survey found that two-thirds of respondents think current levels of reproducibility constitute a “major problem” for science. So far, physics hasn’t been affected much; the crisis has been most severe in fields such as psychology and clinical research, which, not coincidentally, involve messy human beings rather than nice clean atomic systems. However, that doesn’t mean it’s irrelevant to physicists. Last month, I had the pleasure of speaking to three physics graduates who have become personally involved in addressing the reproducibility crisis within their chosen profession: medicine.

Henry Drysdale, Ioan Milosevic and Eirion Slade are third-year medical students at the University of Oxford. All three earned their undergraduate degrees in physics, and they now make up one-third of COMPare – an initiative by Oxford’s Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine (CEBM) that tracks “outcome switching” in clinical trials. As Drysdale explained to me over coffee in an Oxford café, researchers who want to perform clinical trials have to state beforehand which “outcomes” they intend to measure. For example, if they are trialling a new drug to treat high blood pressure, then “blood pressure after one year” might be their main outcome. But researchers generally keep track of other variables as well, and often their final report focuses on a positive result in one of these other parameters (a dip in the number of heart attacks, say), while downplaying or ignoring the drug’s effect on the main outcome.

View all posts by this author | View this author's profile

Finding innovation in space

Way to go: Carlton House Terrace. (CC BY-SA 2.0 Richard Croft)

By Margaret Harris

I have a mental block about Carlton House Terrace. This elegant little street in central London is home to several of the UK’s national academies, including the Royal Society and the Royal Academy of Engineering (RAEng), and I’m sure I’ve visited it at least half a dozen times. Yet somehow, whenever I emerge from Charing Cross underground station in the middle of Trafalgar Square, I never know which way to go next.

Fortunately, this is the 21st century, so when the usual disorientation struck me yesterday on my way to an “Innovation in Space” event at the RAEng, I simply pulled out my smartphone. Within seconds, an app told me exactly where I was (plus or minus a few metres) and how to walk from there to 3 Carlton House Terrace. Minutes later, I was safely ensconced in the seminar room, nodding in agreement as the event’s chair, Sir Martin Sweeting, explained how space-related innovations – including, ahem, the network of satellites that make up the Global Positioning System (GPS) – have become an integral part of our daily lives.

View all posts by this author | View this author's profile

Something more concrete

A sample of asphalt to which steel-wool fibres have been added, making the material magnetic.

By Margaret Harris at the AAAS Meeting in Washington, DC

Although Thursday’s LIGO result was extremely exciting, I’m afraid I can only spend so much time pondering ripples in the fabric of space–time before I start yearning for something a little more…concrete. Like, well, concrete. And asphalt. And cement. These decidedly ordinary materials were the stars of two of the most fascinating talks I’ve seen at the AAAS meeting here in Washington DC over the past two days.

First up was Erik Schlangen, a civil engineer at the Delft University of Technology in the Netherlands who develops “self-healing” materials. One of his projects (which you can watch him demonstrate in a TED talk) involves mixing porous asphalt with fibres of steel wool. The resulting conglomerate is magnetic (that’s a magnet sticking to it in the photo), which means that microscopic cracks in it can be repaired using induction heating. The heat melts the bitumen in the asphalt, allowing it to re-fuse, but the surrounding aggregate remains relatively cool – meaning that cars can be driven over asphalt road surfaces almost as soon as the repair is complete.

View all posts by this author | View this author's profile