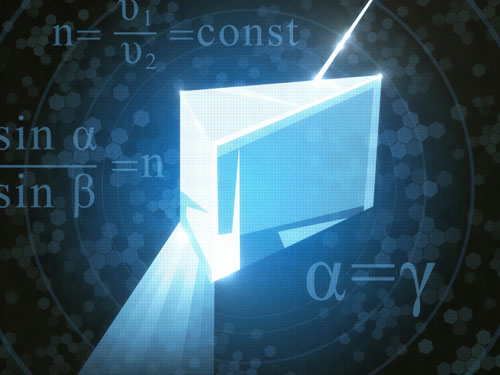

Shining a light on teaching physics. (Courtesy: iStockphoto/Greyfebruary)

By James Dacey in Córdoba, Argentina

There has been a lot of fancy language flying around here at the International Conference on Physics Education (ICPE), which is taking place in Córdoba. Words such as “pedagogy” and “metacognition” roll off the tongues of education researchers as naturally as a particle physicist at CERN saying the words “Higgs boson”.

At first it seemed a bit like a foreign language to me, but I’ve started to realize that one of the recurring ideas at the conference can be described in more everyday terms: thinking about thinking. Teachers should think about the way they think about learning, and the way their students think about learning.

Let me explain.

A good example of this was the meeting’s headline event – the keynote talk given by Cedric Linder, a pioneer who scooped this year’s ICPE medal for outstanding contributions to physics-education research. Linder gave a passionate talk in which he called on physics teachers to adopt a “discursive view” of learning physics. The researcher, who is based at Uppsala University in Sweden, spoke of the pitfalls when teachers make assumptions about their students’ prior understanding. He talked about how physics language is both present and apresent when physics objects are taught through the use of educational texts.

Now, an education researcher may have understood that last sentence, but I for one had to go away and think about it. In fact, Linder kindly agreed to sit down with me and give me something of an idiot’s guide to his research, which I’ll now share with you.

He gave the example of the classic schoolbook diagram of a light ray bending as it passes from air into a medium with a different refractive index. This diagram is used time and again as a way of teaching students the phenomenon of refraction (the “physics object” in his jargon). Linder’s point is that educators at various levels often wrongly assume that students know and understand the language and the concepts that are not being shown in the diagram (the physics “text”). This includes the fact that the light ray is a line perpendicular to the wavefronts.

In arguing for a more “discursive” approach to physics education, Linder does offer some practical advice for teachers. In particular, they should always think about when it is appropriate to unpack the hidden information in diagrams and standard textbook explanations of physics concepts. In doing so, it will help both the teachers and the students to develop the language of physics and work towards what Linder describes as a “disciplinary fluency”.

Too often, says Linder, teachers view the class as a one-way transmission of information from them to the students. In his discursive approach, the learning comes precisely from those interactions/struggles with the concepts, which can lead to that moment when the students suddenly see the world differently.

I hope that makes sense!

Yes! I know exactly what you mean, I experienced it myself in school, more than once.

Sounds a lot like incommensurability in philosophy, see Thomas Kuhn and Paul Feyerabend. It is a problem, since scientists and teachers are not aware of it or is misinterpreting it.