Tag archives: dark matter

What can cosmic rays tell us about dark matter?

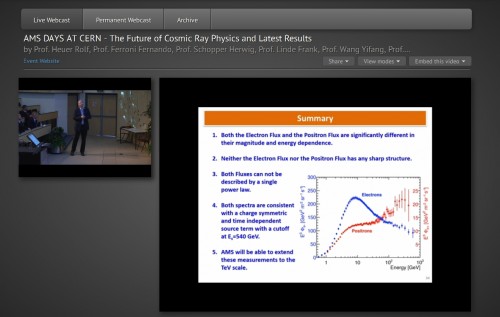

Alive and well: the positron excess as seen by the AMS. (Courtesy: CERN)

By Hamish Johnston

Cosmic rays, dark matter and other astrophysical mysteries are being debated with much vigour at a three-day conference that began this morning at CERN in Geneva. Called “AMS Days at CERN”, the meeting will include presentations of the latest results from the Alpha Magnetic Spectrometer (AMS).

Located on the International Space Station, the AMS measures the energy of high-energy charged particles from the cosmos – otherwise known as cosmic rays. These particles are of great interest because they offer us a window into some of the most violent processes in the universe. Some cosmic rays have probably been accelerated during supernova explosions while others could be produced as matter is sucked into the supermassive black holes that lie at the centres of many galaxies.

View all posts by this author | View this author's profile

The July 2014 issue of Physics World is out now

By Matin Durrani

Unless you’re prepared to modify our understanding of gravity – and most physicists are not – the blunt fact is that we know almost nothing about 95% of the universe. According to our best estimates, ordinary, visible matter accounts for just 5% of everything, with 27% being dark matter and the rest dark energy.

The July issue of Physics World, which is out now in print and digital formats, examines some of the mysteries surrounding “the dark universe”. As I allude to in the video above, the difficulty with dark matter is that, if it’s not ordinary matter that’s too dim to see, how can we possibly find it? As for dark energy, we know even less about it other than it’s what is causing the expansion of the universe to accelerate and hence making certain supernovae dimmer (because they are further away) than we’d expect if the cosmos were growing uniformly in size.

BOSS uses 164,000 quasars to map expanding universe

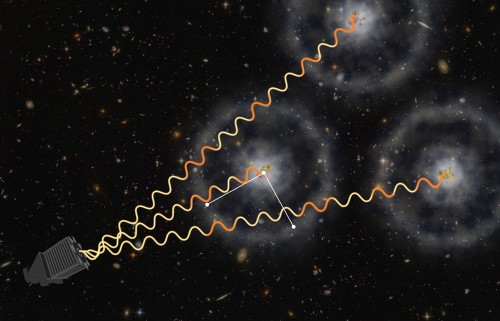

An artist’s illustration of how BOSS uses quasars to measure the distant universe. (Courtesy: Zosia Rostomian, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory; Andreu Font-Ribera, BOSS)

By Calla Cofield at the APS April Meeting in Savannah, Georgia

Scientists looking at data from the Baryon Oscillation Spectroscopic Survey (BOSS), the largest programme in the third Sloan Digital Sky Survey, have measured the expansion rate of the universe 10.8 billion years ago — a time prior to the onset of accelerated expansion caused by dark energy. The measurement is also the most precise measurement of a universal expansion rate ever made, with only 2% uncertainty. The results were announced at a press conference at the APS’s April meeting on Monday, at the same time that the results were posted on the arXiv preprint server.

The rate of universal expansion has changed over the course of the universe’s lifetime. It is believed to have gradually slowed down after the Big Bang, but mysteriously began accelerating again about 7 billion years ago (by rippstein). BOSS and other observatories have previously measured expansion rates going back 6 billion years.

A possible dark-matter bubble

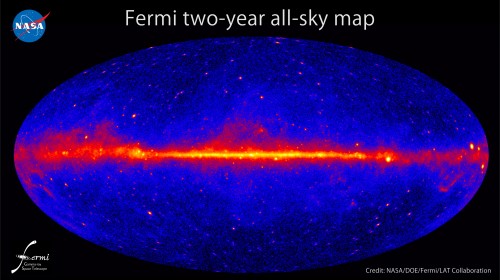

This all-sky image, constructed from two Fermi datasets, shows how the gamma-ray sky appears at energies greater than 1 GeV. (Courtesy: NASA/DOE/Fermi/LAT Collaboration)

By Calla Cofield at the APS April Meeting in Savannah, Georgia

The American Physical Society (APS) April meeting has been taking place in Savannah, Georgia, for the past three days. On Saturday, Tracy Slatyer from MIT spoke to reporters about a paper that she and colleagues posted on arXiv in February, in which they suggest that a mysterious excess of gamma rays surrounding the galactic centre could be explained as dark-matter particle annihilation.

The researchers use what Slatyer calls a “simple” model of dark matter, in which the invisible substance is made up of weakly interacting massive particles (WIMPs) with a mass of about 35 GeV. The model predicts that WIMPs may collide with each other and annihilate, producing gamma rays and either b-quarks or some other mixture of quarks. The Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope surveys the entire observable sky for the presence of gamma rays. Fermi’s observation of the plane of the Milky Way revealed that our galaxy is bright with gamma rays, but Fermi has not been able to identify the sources of all those powerful photons. Gamma-ray excesses (more than can be explained by known sources) near the galactic centre have been identified in the Fermi data in the past – most notably at about 130 GeV.

The work presented by Slatyer and her colleagues identifies an excess of gamma rays between 1 and 3 GeV. The researchers say they can see a distinctly spherical, bubble-like collection of photons. Slatyer told reporters that based on the dark-matter model, this spherical shape is not a coincidence – the dark-matter annihilation theory does not hold for a more stretched-out, elongated cluster of gamma rays; nor would it hold if the bubble were not at the centre of the galaxy.

Are ‘sterile neutrinos’ dark-matter particles after all?

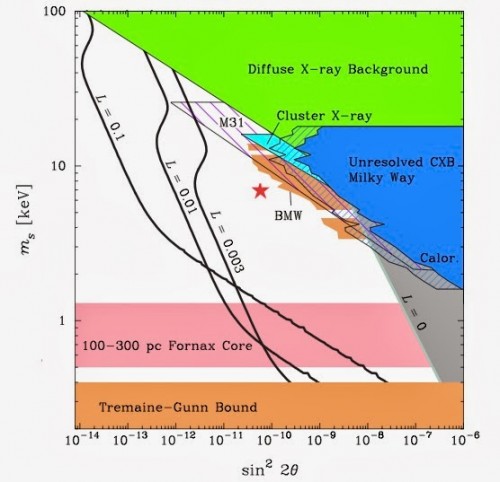

Could sterile neutrinos constitute dark matter? (Courtesy: Bubul et al./ arXiv:1402.2301)

By Tushna Commissariat

It is always interesting to us at Physics World when a particular topic suddenly attracts the attentions of the physics community, especially when it’s a rather hotly debated subject. The past couple of days, for example, have seen a lot of talk about “sterile neutrinos”, based on two papers – published in quick succession on the arXiv preprint server – that suggest the tentative detection of these hypothetical paricles.

Both papers are based on an unidentified emission line seen in the X-ray spectrum of some galaxy clusters obtained by the European Space Agency’s XMM-Newton observatory. Intriguingly, sterile neutrinos are also considered to be possible dark-matter candidates, meaning that – if discovered – they would be the first fundamental particles to lie beyond the bounds of the Standard Model of particle physics.

A new way to look for axions

By Hamish Johnston

There’s an interesting preprint on the arXiv server that proposes a new way of detecting dark-matter particles. I’ve been thinking about dark matter because last week physicists working on the LUX experiment announced that the underground detector had failed to find any dark-matter particles in the first three months of its operation. LUX was designed to look for WIMPs (weakly interacting massive particles), but WIMPs are not the only game in town when it comes to dark matter. There are also axions, which are the quarry of this latest proposal by three physicists in the US.

Axions are hypothetical particles that were first postulated in the 1970s to help explain puzzling aspects of quantum chromodynamics, which is the theory that describes interactions between quarks and gluons. Axions are also interesting from a cosmological point of view because they have mass but do not interact strongly with electromagnetic radiation. These properties make them prime candidates for dark matter, a mysterious substance that appears to make up most of the matter in the universe.

View all posts by this author | View this author's profile

Physics World 2013 Focus on Big Science is out now

By Michael Banks

Physics World Focus on Big Science.

All eyes will be on Stockholm next week as the 2013 Nobel Prize for Physics is announced. One of the frontrunners for the prize in the minds of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences will surely be the discovery last year of the Higgs boson at CERN’s Large Hadron Collider (LHC).

But the LHC story is far from over and in the latest Physics World focus issue on “big science” find out how the LHC will hunt for new particles beyond the Higgs boson once the collider restarts in 2015 following an 18-month repair and upgrade programme at the Geneva-based lab.

All full members of the Institute of Physics will receive a print edition of the focus issue along with their copy of the October issue of Physics World, but everyone can access a free digital edition. The focus issue also looks at how particle physicists are already thinking about what could come after the LHC, with bold plans for a 80–100 km proton–proton collider. There are even plans for a collider based on lasers, with an international team looking at creating an array of “fibre lasers” to be used as a future “Higgs factory”.

Are CDMS and XENON both right about dark matter?

Part of the XENON100 experiment: does it agree with CDMS? (Courtesy: XENON)

By Hamish Johnston

A week or so ago the CDMS experiment in the US reported the detection of three possible dark-matter particles. While that might not sound like much, it is the best evidence yet that dark matter – mysterious stuff that appears to make up one quarter of the mass/energy of the universe – can be detected directly.

But as I said in an earlier blog entry, the detection further muddies the waters in terms of our understanding of exactly what dark matter is. Different experiments say very different things about its possible properties, and now a team of physicists in Denmark, the UK and Switzerland have uploaded a preprint on the arXiv server that tries to make sense of some of this speculation and contradiction.

View all posts by this author | View this author's profile

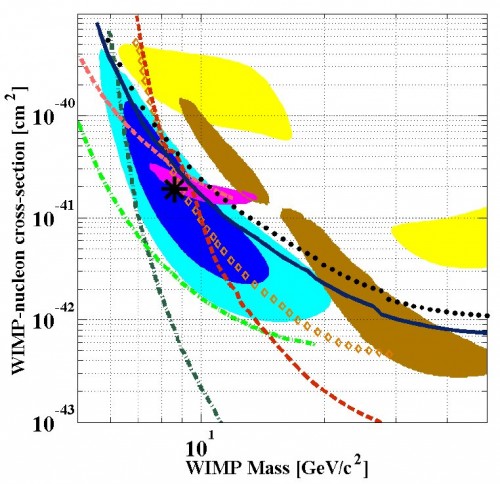

Has CDMS glimpsed dark matter?

Dark matter search results. The best fit to the CDMS result is the located at the black asterisk. The Xenon exclusion region is to the right of the green dashed lines. (Courtesy: CDMS)

By Hamish Johnston

Physicists working on the Cryogenic Dark Matter Search (CDMS) may have spotted three dark-matter particles in data from a detector deep beneath the North Woods of Minnesota. The measurement has a statistical significance of about 3σ – which is a long way from the gold standard of 5σ that usually heralds the discovery of a new particle. That said, this result is the best evidence yet that dark matter could be detected directly as it passes through the Earth.

View all posts by this author | View this author's profile

First results due from AMS

By Michael Banks in Boston

The first results from the $1.5bn Alpha Magnetic Spectrometer (AMS) are expected to be released in the coming two weeks, according to AMS principal investigator Samuel Ting.

Ting, who shared the 1976 Nobel Prize for Physics, was speaking at the 2013 AAAS meeting in Boston.

View all posts by this author | View this author's profile