Bright spark: Giana Phelan of OLEDWorks shows-off some of the company’s wares.

By Robert P Crease in New York

“One well-lit place” is the best way to describe the exhibition hall at Javits Center in New York when it opened on Tuesday morning. I fully expected to be bedazzled at every turn because the venue is hosting LIGHTFAIR, the world’s largest lighting technology trade fair, and so the hall is packed with more than 600 booths designed to highlight, so to speak, the world’s lighting revolution.

That revolution was set in motion by the development, two decades ago, of the blue LED. Blue LEDs – combined with red and green – made it possible for white LED lights to compete with traditional incandescent light bulbs. Because LEDs consume only a fraction of the energy of incandescents, it is only a matter of time before the revolution is complete.

As I wandered through LIGHTFAIR’s exhibition booths, I saw the state-of-the-art of this revolution’s progress. The only things standing in the way of LEDs’ complete triumph, most exhibitors told me, was a certain instability in the colour quality of LED light, some heat-removal issues, and the development of larger and more flexible surface illumination. A lighting engineer friend of mine said that the end of the revolution will occur when LEDs are good enough to replace the familiar MR-16 halogen lamp – which have long been literally a fixture in boutiques where they are often used to spotlight merchandise.

A few booths featured lighting incorporating lenses to compensate for slight variations in the colours of LED lighting. At least a dozen booths had OLEDs, or organic light-emitting diodes. Giana Phelan, the director of business development at OLEDWorks, explained to me that these consist of a thin layer of organic material sandwiched between two electrodes, which emit light when a current is passed through. “The rest is packaging,” she said, pointing to her booth’s array of samples. An advantage over LEDs, which are point sources, is that OLEDs are surfaces and can be made bendable.

Some booths had multipurpose light fixtures that integrated different kinds of sensors: traffic, noise, weather, environment quality, parking, security, and so on. Other booths showed off different kinds of lighting for indoor, outdoor, underwater, theatre, sports and city use.

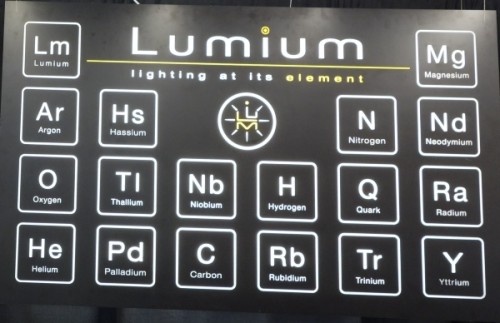

Elemental: Lumium’s periodic table of lighting.

I was drawn to Lumium’s booth, which exhibited a range of hi-tech lights each of which, it was claimed, was named after a chemical element. “Quark?” I asked. “Ah,” said co-founder Jordan Kloos, “you are smart!” I asked why he had chosen that name for that particular fixture. “It’s small,” he said, pointing overhead to one, “and as basic as you can get!”

One LIGHTFAIR speaker was Charles Hoberman, an innovative designer and engineer whose “Hoberman sphere” is surely now in every child’s toybox. It was entertaining to hear him utter engineering phrases such as “adaptive fritting” and “emergent surfaces”, when I had no idea what they meant. I loved his final remark: “I always try to think of some message to end on, and I never can.”

“I always try to think of some message to end on, and I never can!”, but Robert, you did have about the LIGHTFAIR that “light lamps” are going fast to being very effiecient and heatlessly the coolest possible.

Trackback: Physics Viewpoint | Bright lights, big city: a lighting revolution comes to New York