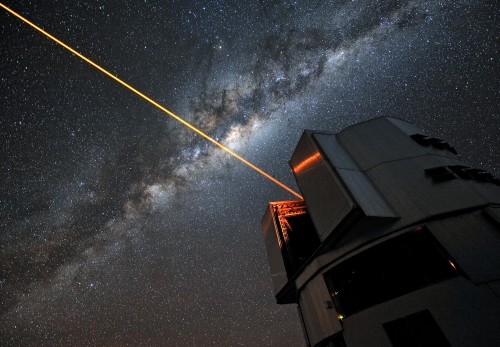

Not bright enough: this adaptive-optics laser would have to be a million times brighter to cloak the Earth. (Courtesy: ESO/G Hüdepohl)

By Hamish Johnston

Sometimes, the biggest laughs on April Fools’ Day come from the stories that read like hoaxes but are actually true. One such item is a proposal by David Kipping and Alex Teachy of Columbia University in the US, who have come up with a way of hiding the Earth from aggressive civilizations on distant planets (at least I think this is real, but I wouldn’t be surprised if it were an elaborate hoax!).

Last month we published the news article “Where to look for signals from alien astronomers with a good view of Earth”, which points out that there are about 100,000 planetary systems out there that would see the Earth as it passes in front of the Sun. This transit would tell an alien civilization that the Earth is in the habitable zone of the Sun and could be a good candidate for colonization – if that’s what advanced alien civilizations do.

To avoid alien invasion, Kipping and Teachy propose firing a laser into space to make up for the small amount of sunlight that is blocked by the Earth during a transit, thereby rendering us invisible to alien astronomers. All it would take to fool an instrument like our own Kepler space telescope is a 30 MW laser fired continuously for 10 hours per year. Give that today’s most powerful continuous-wave lasers can deliver about 1 MW for just a minute or so, this is not something we could do tomorrow. And that just hides us from one alien telescope, leaving 100,000 more potential systems out there to worry about. Their proposal is described in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society: “A cloaking device for transiting planets”.

Now for a few of the funnier physics-related hoaxes we have come across today. That famous Swiss sense of humour is all over CERN’s 1 April gag, which involves a surprise discovery, made – or actually heard – when data from the Large Hadron Collider are converted into sound. So, put on your cans and enjoy the video above.

London’s Royal Albert Hall announced that its famous oval building has been transformed into a particle collider dubbed the “Small Halldron Collider”. The idea began as a joke by television physicist Brian Cox, who was apparently horrified to discover that Albert Hall staff took him seriously.

“Don’t trust everything you read on the arXiv” is good advice, especially on 1 April. A case in point is a paper called “Pi in the sky” by Ali Frolop and Douglas Scott of the University of British Columbia in Canada. Scott (who really exists) and Frolop publish one paper a year, and their 2016 offering combines numerology with the cosmic microwave background.

The “thudding sound” of the LHC data at CERN is quite different from the soft “0.2 sec whisper” of the LIGO’s data of gravitational waves from the distant colliding binary black holes.

Trackback: Blog - physicsworld.com