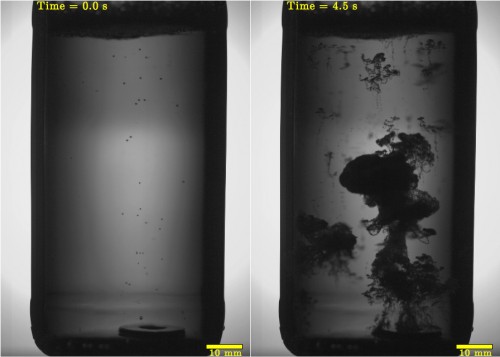

A foamy mess in the making. (Courtesy: Javier Rodríguez-Rodríguez)

By Hamish Johnston

We’ve all had a friend who does it – you’re deep in conversation at a party, beer bottle in hand, when someone sneaks up and taps the top of your bottle with theirs, causing a foamy mess to erupt from your bottle. And to add insult to injury, their bottle doesn’t foam.

Now, physicists in Spain and France have studied this curious effect and gained a better understanding of how it occurs. While their work won’t prevent wet shoes and slippery floors at university social gatherings, the researchers believe their work could provide insights into geological features such as oil reservoirs, mud volcanoes and “exploding lakes”.

The soggy process begins when the bottle is struck from above, causing a compression wave to travel down the glass – according to Javier Rodríguez-Rodríguez and Almudena Casado-Chacón of Carlos III University of Madrid and Daniel Fuster of Université Pierre et Marie Curie, who did this latest research.

When the wave reaches the bottom of the bottle, it pushes the base of the bottle downwards, causing a drop in pressure in the liquid near the bottom. This triggers a low-pressure “rarefaction wave” that travels upwards to the open surface of the liquid. As this wave passes through the liquid, the pressure drop allows carbon dioxide to come out of the solution and form relatively large “mother” bubbles.

When the wave reaches the surface, it reflects back down the bottle as a high-pressure compression wave. When the compression wave encounters a mother bubble, the bubble implodes in a well-known process called cavitation. Rodríguez-Rodríguez and colleagues say that these implosions cause large numbers of very small “daughter” bubbles to form. Because the daughters have a larger surface-to-volume ratio than the mothers, they are able to expand rapidly, turning much of the liquid into a buoyant foam that rushes upwards. In the above time-sequence of images, you can see a plume of bubbles rising a few seconds after the bottle was tapped.

“Buoyancy leads to the formation of plumes full of bubbles, whose shape resembles very much the mushrooms seen after powerful explosions,” Rodríguez-Rodríguez explained. As the bubbles expand they rise more rapidly and form “buoyant vortex rings”. As these accelerate upwards, the bubbles capture more carbon dioxide from the liquid, which increases the volume of the foam.

So why doesn’t the prankster’s bottle foam as well? Rodríguez-Rodríguez explains that a clink on the bottom of the bottle doesn’t produce the initial large rarefaction wave that is crucial for creating the mother bubbles. “If you hit the bottle from below, you first trigger a compression wave and then a somewhat less intense expansion one, which is not very efficient in terms of driving bubble implosion,” he told me.

Although the physics of beer is of crucial importance to many of us, Rodríguez-Rodríguez says that the team’s work also provides insights into why plumes of carbon-dioxide bubbles sometimes form in oil-laden porous rock and other geological formations. Indeed, understanding why this occurs could help geologists find appropriate sites for the underground storage of atmospheric carbon dioxide.

Rodríguez-Rodríguez and colleagues presented their results yesterday at the annual meeting of the American Physical Society Division of Fluid Dynamics in Pittsburgh, US. You can read an extended abstract here: “Why does a beer bottle foam up after a sudden impact on its mouth?“.

The foaming up of a beer bottle due to the “tapping” on its open head is indeed due to the caviating process. However, for a given beer-bottle, for caviating to be effective, the tapping has to create a minimum pressure gradient of some bars along the bottle as the recent caviating work on water shows.