Tag archives: environment

Our hazardous planet: when the world is out to get you

By Matin Durrani

By Matin Durrani

For people afflicted by last month’s devastating fire at Grenfell Tower in London or for those caught up in recent terrorist atrocities, it can seem that many problems in this world are entirely of our own making.

Yes the modern world has benefited from our collective wisdom and creativity – especially through science and engineering – but often it feels as if irrational human behaviour lies at the root of many of our troubles.

Nevertheless, we should remember that our planet itself holds many natural hazards too, as the latest special issue of Physics World reminds us.

Remember that if you’re a member of the Institute of Physics, you can read Physics World magazine every month via our digital apps for iOS, Android and Web browsers.

View all posts by this author | View this author's profile

Designing smarter cities

By James Dacey in Berkeley, US

This weekend politicians at the COP21 summit in Paris signed a landmark legal agreement to keep global temperature rises at bay by curbing carbon emissions. The tricky next question of course is: how are we actually going to do this? In this short video, civil engineer Arpad Horvath of the University of California Berkeley explains that one of the aspects will be a fundamental rethink of our urban infrastructures. Horvath believes we need to move towards “smart cities” with smaller carbon footprints at all levels – from greener individual buildings, to more sustainable transport networks.

The July 2015 issue of Physics World is now out

By Matin Durrani

Sometimes, nature does something unexpected – something so rare, transient or remote that only a lucky few of us get to see it in our lifetimes. In the July issue of Physics World, we reveal the physics behind our pick of the weirdest natural phenomena on our planet, from dramatic rogue waves up to 30 m tall, to volcanic lightning that can be heard “whistling” from the other side of the world, and even giant stones that move while no-one is watching. We also tackle tidal bores on rivers and the odd “green flash” that is sometimes seen at sunset.

Plus, we’ve got six fabulous full-page images of a range of weird phenomena, including salt-flat mirrors, firenadoes, “ice towers”, beautifully coloured nacreous clouds, mysterious ice bubbles of gas trapped in columns, as well as my favourite – the delicately wonderful “frost flowers” seen very occasionally on plants.

Personal reflections on Plutopia

By Margaret Harris

As Physics World’s reviews editor, I come across a lot of books that interest me intellectually. But with Kate Brown’s book Plutopia – the subject of this month’s Physics World podcast – my interest is personal, too.

Brown’s book tells the story of two cities, Richland in the US and Ozersk in the former Soviet Union, that were built to house workers at the nearby Hanford and Maiak plutonium plants. Brown calls these cities “plutopias” because high wages and subsidies meant that residents enjoyed a better standard of living than their neighbours outside the secure zones. Such benefits, in turn, fostered an atmosphere of loyalty and solidarity that helped keep the plants’ horrendous environmental records under wraps.

This sounded familiar to me because my childhood had a decidedly “plutopian” flavour. Although I didn’t grow up in an “atomic city” like Richland or Ozersk, my father worked for a defence contractor for 39 years, and his plant’s generous vacation allowance meant that we took longer holidays than most American families. We had good health insurance, too, which may have saved my life as a teenager. But after reading Plutopia and speaking to Brown for the podcast, I found myself wondering whether such benefits were a fair trade for working, as my father and thousands of others did, in a mostly windowless building that was surrounded by razor wire and contaminated with beryllium dust.

View all posts by this author | View this author's profile

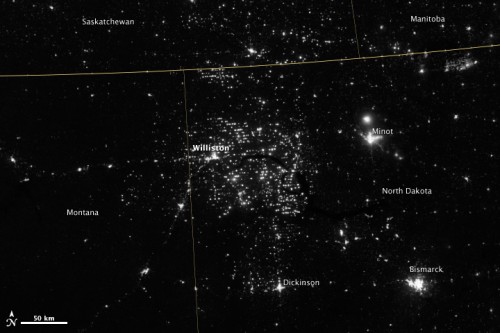

Burning the midnight gas

The light from natural gas flares burning in North Dakota’s Bakken oil field can be seen from space. (Courtesy: NASA Earth Observatory)

By Margaret Harris in Chicago

The environmental risks of shale-gas production are real, but the things people worry about most aren’t necessarily the ones that cause the most damage. That was the message of this morning’s AAAS symposium on “Hydraulic Fracturing: Science, Technology, Myths and Challenges”, which featured talks on the social implications of hydraulic fracturing as well as the risks of water and air contamination.

Hydraulic fracturing, or “fracking”, involves drilling a well and filling it with a high-pressure mixture of water and other chemicals. These high pressures cause nearby rock formations to fracture, releasing trapped oil and gas. According to the first speaker, energy consultant David Alleman, fracking and horizontal drilling have “revolutionized the energy picture in the US”: a few years ago, the country imported 60% of the oil it consumed, but today the figure is just 30%.