By Tushna Commissariat

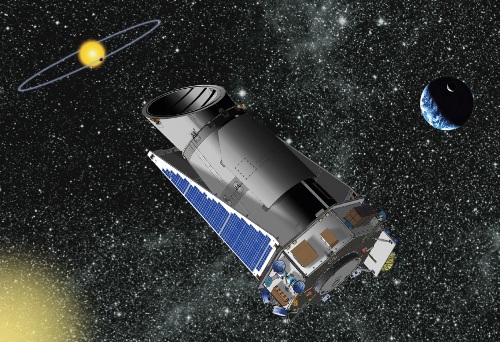

NASA’s Kepler space telescope. (Courtesy: NASA)

To much general dismay, earlier this month NASA officials announced that their Kepler space telescope had gone into a self-imposed “safe mode”, something that the telescope is programmed to do if one of its primary systems is not fully functional. Although the telescope was then rebooted, it shut down again this week and it seems that all is definitely not well with our favourite exoplanet spotter: the mission collaboration announced that the instrument has suffered a critical failure and may never be fully operational again.

The problem seems to lie with the four pesky gyroscope-like “reaction wheels” that help the telescope remain steady and pointed in a particular direction. Last July, one of the wheels ceased to work thanks to a lubrication issue, and it was “retired.” Luckily, although the telescope was kitted out with four wheels, it was designed to run on three at any given point. Of course, you see where this is going now – the recent mishaps have seen a structural failure in another one of the wheels, hobbling the telescope for good, or so it may seem. In its mission update, the Kepler team says that “with the failure of a second reaction wheel, it’s unlikely that the spacecraft will be able to return to the high pointing accuracy that enables its high-precision photometry. However, no decision has been made to end data collection.” It is good to remember, though, that Kepler completed its primary three-and-a-half-year mission, with extreme success one might add, last November, and is now within its extended mission phase.

An image of a “reaction wheel”. (Courtesy: NASA/ Ball Aerospace and Tech. Corp.)

But it’s not all done and dusted. “I wouldn’t call Kepler down and out just yet,” says John Grunsfeld, a NASA administrator and one-time astronaut who carried out five servicing missions on the Hubble Space Telescope. The Kepler team will now put the telescope into a “Point Rest State” – a sort of induced coma where the craft reduces its fuel consumption and slumbers until researchers are sure how to proceed – meaning the team could have anywhere between months and years before the telescope shuts down completely, according to the mission update.

If you are wondering what the team could do to possibly salvage the instrument, Scott Hubbard of the Stanford School of Engineering, who previously served as director of NASA Ames Research Center during much of Kepler’s construction, came up with two possible suggestions. First, he suggests turning on the wheel that was switched off last year. “It was putting metal on metal, and the friction was interfering with its operation, so you could see if the lubricant that is in there, having sat quietly, has redistributed itself, and maybe it will work,” he says. His second suggestion is a bit more complex and has never been tried before, according to him, but could help. It involves using thrusters and the solar pressure exerted on the solar panels to try and act as a third reaction wheel and provide additional pointing stability. “I haven’t investigated it, but my impression is that it would require sending a lot more operational commands to the spacecraft,” says Hubbard.

While it remains to be seen if this eye in the sky will come to life once more, researchers currently have more than a year’s worth of Kepler data that are yet to be analysed, which will surely keep intrepid exoplanet hunters busy for a while.

The image caption should be corrected to “reaction wheel”. The three instances in the article body are correct.

The caption has now been updated; thank you.

Trackback: Blog - physicsworld.com