By James Dacey

“Brevity is a great charm of eloquence,” said the great Roman orator Cicero. A new study published today suggests that researchers would be wise to follow Cicero’s advice when it comes to choosing a title for their next academic paper. Data scientists at the University of Warwick in the UK analysed 140,000 papers and found that those with shorter titles tend to receive more citations.

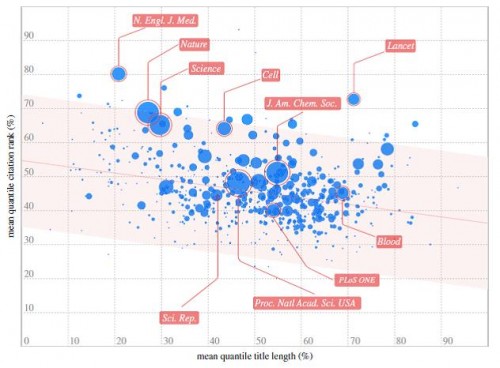

Similar studies have been carried out in the past leading to contradictory results. But Adrian Letchford and his colleagues have used two orders of magnitude more data than previous investigations, looking at the 20,000 most cited papers published each year between 2007 and 2013 in the Scopus online database. Publishing their findings in Royal Society Open Science, Letchford’s group reports that papers with shorter titles garnered more citations every year. Titles ranged from 6 to 680 characters including spaces and punctuation.

Of course there are many factors other than title length that could influence how successful a paper will be, and Letchford and team address some of these in the study. For instance, they realize that a journal’s status has a strong bearing on how likely it is to be cited. But after examining the patterns within individual journals within the same timeframe, they found the same trend towards papers with shorter titles doing better.

What might the cause be? The Warwick group suggests three possible explanations. First is that high-impact journals might restrict the length of titles, thus skewing the overall results. Second, incremental research might be published with longer titles in less prestigious journals. Finally, papers with more succinct titles are easier to understand, making them more accessible to a wider audience.

Personally, I think these factors overlap and influence each other. Also, if a work is revolutionary enough, it will gain its recognition no matter what the title is. But as somebody who spends his days trying to translate technical scientific results into clear messages for a wide audience, I find the third explanation the most intriguing. As Einstein said: “If you can’t explain it simply, you don’t understand it well enough.” The same applies to journalism, as nicely argued in this recent Economist article.

But in the end, looking purely at titles and citation numbers is an extremely blunt way of drawing any firm conclusions. So rather than being the final word on the matter, this study (which, incidentally, has the succinct title “The advantage of short paper titles“) could trigger a multitude of follow-up studies. How about breaking things down by discipline? Or why not take a more sophisticated look at the relationship between a paper’s language and its impact – borrowing methods from linguistic studies and the burgeoning field of alt-metrics? Let us know what you think by posting a comment. But remember: keep it brief.

‘Short Paper Titles Sing.’ J-School motto: “Terse, tight, and telegraphic.” Art school dictum: “Less is more.”

Simplicity of language is the most important factor. Statistics may say that the shorter the better. But a writer need not to think about that. If the readers can realize him/her that is the success.

The title has to be like a Japanese Haiko, where the complete poetic texte has only 5+7+5 = 17 syllables.