Tag archives: radiation

Balloon-borne experiment will reveal how cosmic rays damage computer memories

By Tamela Maciel at the APS April Meeting in Baltimore, Maryland

Little bits: the CRIBFLEX logo. (Courtesy: Drexel University Society of Physics Students)

A group of undergraduate students at Drexel University in Philadelphia is ready to click “confirm” on an Amazon order that will include a weather balloon, a memory storage device, a GPS, a Geiger counter and a BeagleBoard computer (described to me as a “beefier version of Raspberry Pi”). For less than $2000, this team of physics, engineering and computer-science students plans to launch a weather-balloon experiment that will measure the effects of cosmic rays on DRAM memory devices at high altitudes.

The team is part of the Drexel University Society of Physics Students and the members presented their experiment design at the April Meeting of the American Physical Society in Baltimore, Maryland, last weekend.

DRAM is a very quick and simple type of electronic memory – each bit takes the form of a capacitor that either has charge or doesn’t, according to whether it’s storing a zero or one. Unfortunately, this simple design can make the bits very sensitive to radioactivity or cosmic rays, which can cause bits to flip values and introduce “soft errors” into the data.

Proton-beam therapy explained

By James Dacey

The story of young brain-tumour patient Ashya King has gripped the British public over the past few weeks, with every twist and turn covered extensively in the media. In a nutshell, the five year old was removed from a hospital in Southampton at the end of August by his parents, without the authorization of doctors. They wanted their son to receive proton-beam therapy, which was not offered to them through the National Health Service (NHS). The family went to Spain in search of the treatment, triggering an international police hunt that subsequently saw the parents arrested before later being released.

The drama was accompanied by a heavy dose of armchair commentary, with Ashya’s parents, the hospital in Southampton and the police all receiving both criticism and praise. Even the British Prime Minister, David Cameron, got caught up in the affair, as he offered his personal support to the parents. To cut a long story short, Ashya’s parents finally got their wish and they have ended up at a proton-therapy centre in the Czech Republic where their son’s treatment begins today.

But what is proton therapy? It is a relatively new medical innovation that shows great promise in the treatment of cancer, though it is only currently available in certain countries. Beams of protons can be directed with precision at tumours in the body – allowing the energy to destroy cancer cells, while causing less damage to the surrounding tissue than is possible with conventional radiation therapies. The treatment, however, is only really useful in specific cases of cancer, such as where is vitally important that surrounding structures are not damaged. And because it is relatively new, there is less information available about how effective it is compared with more established treatments.

View all posts by this author | View this author's profile

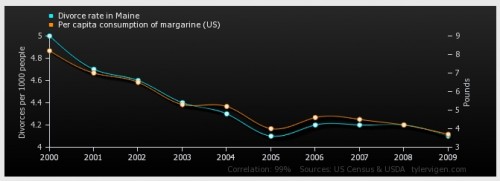

Radiation levels near Fukushima, trust in science and fun with correlations

Do divorcees eat more margarine? Or does the butter substitute break up marriages? (Courtesy: Tyler Vigen)

By Hamish Johnston

This week’s Red Folder begins in Japan, where the 2011 disaster at the Fukushima nuclear power plant continues to cause misery for the 100,000 or so local people who still cannot return to their homes. But who is to blame? Writing in World Nuclear News, Malcolm Grimston of Imperial College London argues that radiation levels in much of the current exclusion zone are no higher than natural levels in other parts of Japan – and much lower than natural levels in some other populated regions worldwide. Grimston concludes that “an overzealous infatuation with reducing radiation dose, far from minimizing human harm, is at the heart of the whole problem”. His article is called “What was deadly at Fukushima?”.

Personal reflections on Plutopia

By Margaret Harris

As Physics World’s reviews editor, I come across a lot of books that interest me intellectually. But with Kate Brown’s book Plutopia – the subject of this month’s Physics World podcast – my interest is personal, too.

Brown’s book tells the story of two cities, Richland in the US and Ozersk in the former Soviet Union, that were built to house workers at the nearby Hanford and Maiak plutonium plants. Brown calls these cities “plutopias” because high wages and subsidies meant that residents enjoyed a better standard of living than their neighbours outside the secure zones. Such benefits, in turn, fostered an atmosphere of loyalty and solidarity that helped keep the plants’ horrendous environmental records under wraps.

This sounded familiar to me because my childhood had a decidedly “plutopian” flavour. Although I didn’t grow up in an “atomic city” like Richland or Ozersk, my father worked for a defence contractor for 39 years, and his plant’s generous vacation allowance meant that we took longer holidays than most American families. We had good health insurance, too, which may have saved my life as a teenager. But after reading Plutopia and speaking to Brown for the podcast, I found myself wondering whether such benefits were a fair trade for working, as my father and thousands of others did, in a mostly windowless building that was surrounded by razor wire and contaminated with beryllium dust.

View all posts by this author | View this author's profile