Tag archives: Standard Model

Great wrong theories, new spin on golf, physics photo competition

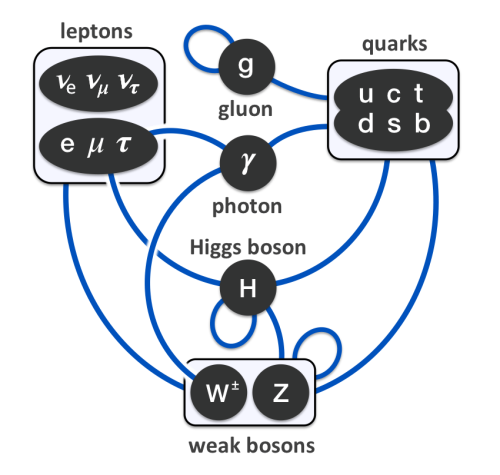

The Standard Model: wrong, but wonderfully wrong (Courtesy: Eric Drexler)

By Hamish Johnston

What is the greatest wrong theory in physics? Physicist Chad Orzel asks that question in his latest blog for Forbes and by wrong he does not mean incorrect, but rather incomplete. He makes the argument for the Standard Model, which he says has been wrong for a very long time – but continues to be phenomenally successful.

View all posts by this author | View this author's profile

And so to bed for the 750 GeV bump

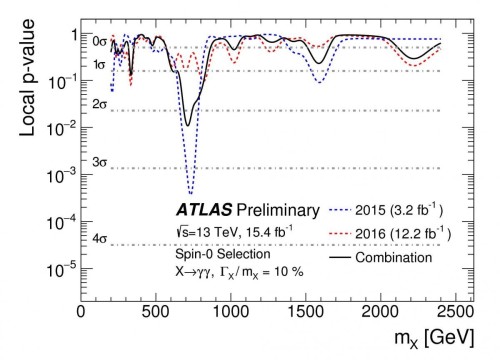

No bumps: ATLAS diphoton data – the solid black line shows the 2015 and 2016 data combined. (Courtesy: ATLAS Experiment/CERN)

By Tushna Commissariat

After months of rumours, speculation and some 500 papers posted to the arXiv in an attempt to explain it, the ATLAS and CMS collaborations have confirmed that the small excess of diphoton events, or “bump”, at 750 GeV detected in their preliminary data is a mere statistical fluctuation that has disappeared in the light of more data. Most folks in the particle-physics community will have been unsurprised if a bit disappointed by today’s announcement at the International Conference on High Energy Physics (ICHEP) 2016, currently taking place in Chicago.

The story began around this time last year, soon after the LHC was rebooted and began its impressive 13 TeV run, when the ATLAS collaboration saw more events than expected around the 750 GeV mass window. This bump immediately caught the interest of physicists the world over, simply because there was a sniff of “new physics” around it, meaning that the Standard Model of particle physics did not predict the existence of a particle at that energy. But also, it was the first interesting data to emerge from the LHC after its momentous discovery of the Higgs boson in 2012 and if it had held, would have been one of the most exciting discoveries in modern particle physics.

‘New boson’ buzz intensifies at CERN, fire prevention in space and Neil Turok on a bright future for physics

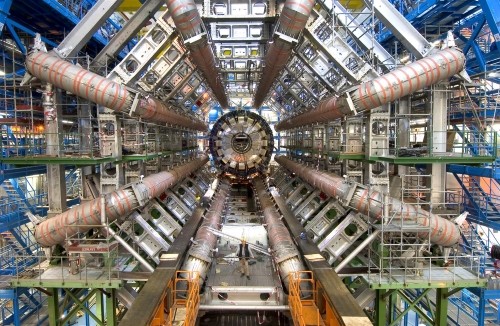

ATLAS under construction: has the experiment gone beyond the Standard Model? (Courtesy: ATLAS)

By Hamish Johnston

Excitement levels in the world of particle physics hit the roof this week as further evidence emerged that physicists working on the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) may have caught sight of a new particle that is not described by the Standard Model of particle physics. If this turns out to be true, it will be the most profound discovery in particle physics in decades and would surely lead to a Nobel prize.

View all posts by this author | View this author's profile

All hail the Standard Model, once again

By Hamish Johnston

I am a condensed-matter physicist by training and sometimes I struggle to get excited by the latest breakthrough in particle physics – usually because most don’t seem much like breakthroughs to me. The latest hot paper from physicists working on the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) at CERN is a perfect example of what I am talking about.

Writing in Nature this week, physicists working on the CMS and LHCb experiments at CERN announced the discovery of a rare decay of the strange B-meson, as well as further information regarding an even rarer decay of the B0-meson. In both cases the decays produce two oppositely charged muons. An animation of how the strange B-meson decay is detected by the CMS appears in the video above.

View all posts by this author | View this author's profile

Is desperation for new physics clouding our vision for new colliders?

By Hamish Johnston

This month marks the 60th anniversary of CERN and to kick-off our coverage here at physicsworld.com, I’m highlighting an essay on the future of collider physics that has just been written by Nobel laureate Burton Richter called “High energy colliding beams; what is their future?“.

Burton Richter warns against desperation. (Courtesy: Stanford University)

Richter shared his 1976 Nobel prize with Samuel Ting for their independent discoveries of the J/ψ meson. He knows his particle colliders, having helped to design and build the world’s first collider in the late 1950s at Stanford University and later directing the Stanford Linear Accelerator Center for 15 years.

Richter believes that the international community is not facing up to tough decisions that must be made about what to do when the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) is retired sometime in the early 2030s. He thinks that “the perspective of one of the old guys might be useful”.

Planning the next huge collider involves the co-operation of three main groups of physicists: those who design and build the accelerators; those who design and build the experiments; and the theoretical physicists who work out what the experiments are looking for. Richter thinks that this is not going well at the moment.

View all posts by this author | View this author's profile

Looking beyond the Standard Model in Liverpool

Liverpool physicist John Fry (right) gets ready for his close-up.

By Hamish Johnston

Earlier this week the Physics World film crew was on Merseyside to document some of the exciting physics done in Liverpool and its environs. Our first stop was a meeting of the NA62 collaboration at the University of Liverpool that was organized by the particle physicist John Fry (above right with our cameraman David Hart).

The finishing touches are currently being put on the NA62 experiment, which will start up at CERN in Geneva next year. The international collaboration running the experiment will focus on making precise measurements of the decay of a charged kaon to a pion and two neutrinos. If all goes to plan, NA62 could find that the decay is not completely described by the Standard Model of particle physics, which could point towards new and exciting physics.

View all posts by this author | View this author's profile

LHCb and CMS see rare decay of the strange B meson

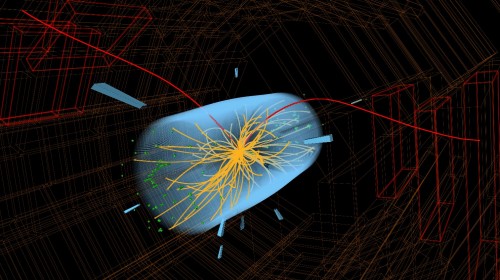

A strange B meson decay event as seen by CMS. (Courtesy: CERN)

By Hamish Johnston

It’s a story with a hint of both “man bites dog” and “dog bites man” about it.

Physicists working on the CMS and LHCb experiments at CERN have independently seen an incredibly rare decay of a particle – a strange B meson decaying into two muons. The odds of this meson decaying in this particular way is about one in a billion, making the joint discovery a triumph of experimental particle physics. And it is officially a discovery. That’s because when data from the two experiments are combined the observation has a statistical significance of greater than 5σ, which is the gold standard in particle physics.

View all posts by this author | View this author's profile

GERDA puts new limit on neutrinoless double beta decay

The GERDA experiment at Gran Sasso. (Courtesy: INFN)

By Hamish Johnston

This stylish chap is looking for an incredibly rare nuclear process called neutrinoless double beta decay. The picture was taken deep under a mountain at Italy’s Gran Sasso National Laboratory, which is about 160 km north-west of Rome. He is standing in a cavern containing the GERDA experiment, which has been searching for the rare decay since 2011.

GERDA hasn’t actually detected a decay event, but the collaboration claims to have measured the best value yet of the lower limit on its half-life in germanium-76. They researchers say that it’s about 2.1 × 1025 years – or 21 yottayears!

View all posts by this author | View this author's profile

The race to find the electric dipole moment

Congress HQ: the University of Montreal actually has an ivory tower!

By Hamish Johnston at the 2013 CAP Congress in Montreal

Yesterday I had lunch with Jeff Martin of the University of Winnipeg, who is a member of an international team that aims to measure the electric dipole moment (EDM) of the neutron at TRIUMF in Vancouver.

Quantum landscaping

Artist’s impression of a map of the Quantum Universe (Graphic courtesy of “ILC — form one visual communication”)

By Tushna Commissariat

Here’s a bit of Friday physics fun… I came across this rather interesting image that shows an artist’s impression of a map entitled “The Quantum Universe”. It includes six landmasses all floating in the Big Bang Ocean; including Dark Matter Landmass, Sypersymmetry Reef, Higgs Island and the Land of Ultimate Unification as well as others.

So go ahead and tell us which island you would like to settle down on. Be sure to look carefully at gems like Newton’s Lawn and Mount Einstein before you make your mind up!

To see a larger hi-res image follow this link.

View all posts by this author | View this author's profile