Tag archives: technology

A glimpse of Einstein in Zurich

A Swiss view: Looking out over Zurich from the rooftop restaurant at ETH Zurich (Courtesy: Sarah Tesh)

By Sarah Tesh

Zurich is one of my favourite cities. Located in the north of Switzerland, it sits at the tip of a glistening, clear lake, with snow-topped mountains in the distance. The buildings are beautiful, the people are friendly and public transport is incredibly efficient. It is also home to multiple world-class science and technology institutes.

So when Physics World was invited to visit two of these facilities, I jumped at the chance to go. Our hosts for the trip were the international organization IBM Research, and ETH Zurich, a STEM-focused university, and the event was a showcase for some of their medical, computer science and quantum-computing research.

View all posts by this author | View this author's profile

Physics of food – the November 2016 issue of Physics World is now out

By Matin Durrani

If you love crisps – and frankly who doesn’t? – you’ll relish the cover feature of the latest issue of Physics World, in which features editor Louise Mayor tours the world’s biggest crisp factory at Leicester in the UK to see how physics is improving production of this yummy salty snack. The issue is now live in the Physics World app for mobile and desktop and will also be made available on physicsworld.com later this month.

Elsewhere in this special issue on physics and food, you can find out how electric fields could help to cut the fact from chocolate and discover why sound holds the key to our appreciation of what we eat.

You can also see how physicists – being masters of data-gathering, modelling and simulation – are ideally placed to develop products that are healthier, more nutritious and make more of our resources. Find out too how soft-matter physicists are crafting “functional” foods that promote feelings of fullness and satisfaction.

View all posts by this author | View this author's profile

Rosetta and bedbugs, LIGO and dark matter, arXiving science and more…

By Tushna Commissariat

Space missions and insects are not the most usual of bedfellows. But in a wonderful example of how space technology can be translated into practical devices for use here on Earth, a UK company has repurposed and adapted an analyser used onboard the Rosetta mission – that in 2014 landed a probe on a comet for the first time – to sniff out bedbugs. The pest-control company, Insect Research Systems, has created a 3D-printed detector that picks up bodily gas emissions from bedbugs – such a device could be of particular use in the hotel industry, for example, where many rooms need to be quickly scanned. The device is based on the Ptolemy analyser on the Philae lander, which was designed to use mass spectroscopy to study the comet’s surface.

“Thanks to the latest 3D-printing capabilities, excellent design input and technical support available at the Campus Technology Hub, we have been able to optimize the design of our prototype and now have a product that we can demonstrate to future investors,” says Taff Morgan, Insect Research Systems chief technical officer, who was one of the main scientists on Ptolemy. In the TEDx video above, he talks about the many technological spin-offs that came from Ptolemy – skip ahead to 13:45 if you only want to hear about the bedbugs, though.

China’s Silicon Valley

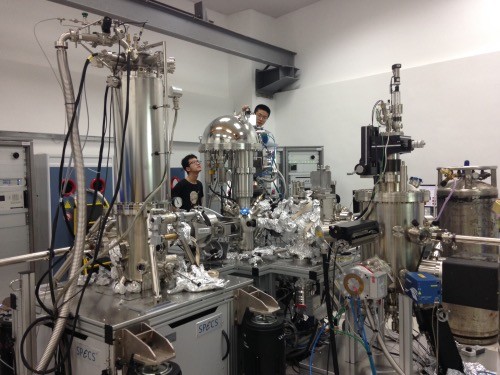

Researchers working on an angle-resolved photoemission spectrometer at the South University of Science and Technology of China.

By Michael Banks in Shenzhen, Guangdong province, China

It is well documented how China seems to be able to build cities within weeks. But how quickly could it build its very own Silicon Valley?

Well, that question may well be answered very soon. Today, I was at the South University of Science and Technology of China (SUSTC), which is located in Shenzhen, Guangdong province.

The university was only created in 2011 and currently the physics department has a sole focus on experimental and theoretical condensed-matter physics, with around 20 undergraduate students each year (that number is expected to rise as the department expands into other areas of physics).

View all posts by this author | View this author's profile

What technologies do you love the most?

By Matin Durrani

Here at Physics World, we’ve had a regular programme of videos since 2009, when I led the way into a brave new multimedia world by interviewing the director-general of CERN Rolf-Dieter Heuer. What Heuer had to say was pretty interesting and the question-and-answer format is a common genre among online videos, but I have to admit that a film of two guys talking to each other while sitting on chairs in an office isn’t the most riveting thing you could ever watch. Even if the chairs were at CERN and one was occupied by the boss of one of the world’s top physics labs.

Since those early days, Physics World has developed and diversified its multimedia efforts, thanks in part to the ideas and inspiration of my colleague James Dacey, who has the rather grand job title of multimedia projects editor. Our content now includes a rolling programme of video documentaries, our 100-second-science strand and even an animation.

View all posts by this author | View this author's profile

Physics World 2014 Focus on Vacuum Technology is out now

By Matin Durrani

Vacuum technology is big business these days, with companies in the sector producing advanced scientific equipment that is vital not only for academic research, but also for manufacturers in other industrial sectors.

In fact, one giant of the vacuum industry – Swedish firm Atlas Copco – bought its UK rival Edwards Vacuum for an eye-watering $1.5bn last year.

If you want to find out more about why Atlas Copco forked out so much cash, don’t miss the latest Physics World focus issue on vacuum technology, which includes an interview with Geert Follens, president of Atlas Copco’s newly created vacuum-solutions division. In the interview, Follens discusses the takeover in more detail and explains why he expects further strong growth in the vacuum market.

Elsewhere in the issue, you can read about a European Union project uniting academia and industry to improve vacuum metrology for production environments. Such efforts are vital even in the drinks industry, where the Van Pur brewery in Poland, for example, uses equipment from KHS Plasmax to coat the inside of bottles with an ultrathin layer of glass using plasma impulse chemical vapour deposition under vacuum.

View all posts by this author | View this author's profile

Eyeing light pollution

By Tushna Commissariat

The newly patented all-sky camera (Courtesy: University of Granada)

Researchers in Spain have developed a small and light device that can quickly and accurately measure the light-pollution levels or artificial night-sky background brightness for a given location. The team, led by Ovidio Rabaza from the Department of Civil Engineering at the University of Granada, has developed a portable system that includes an all-sky camera and several interference filters that can be easily transported and can be used anywhere.

Currently, methods to measure light pollution that affects the night sky involve using complex techniques such as astronomical photometry, which requires large-scale and expensive equipment generally housed in observatories, according to the researchers. According to the team, the new system is “clearly innovative because, for the first time, relative irradiance and sky background luminance have been measured through wide-field images, of all the sky, instead of using more conventional methods”.

View all posts by this author | View this author's profile

Which Nobel-prize-winning physics invention has had the most profound impact on society?

By James Dacey

Physics has brought transformative inventions. (Courtesy: iStockphoto/Péter Mács)

Earlier this week my colleague reported the death of Heinrich Rohrer, the Swiss condensed-matter physicist who shared the 1986 Nobel Prize for Physics for the invention of the scanning tunnelling microscope (STM) at IBM’s Zürich Research Laboratory. Rohrer shared one half of the prize with his IBM colleague Gerd Binnig, while the other half went to the West German Ernst Ruska for his invention of the electron microscope (EM).

By bringing into view the atomic world, EMs and STMs have undoubtedly had a huge impact on science. Before their invention, optical microscopy had been a truly transformative technology. But it had been fundamentally limited to seeing things that are (roughly speaking) larger than the wavelength of the light used to produce the image. And since the wavelength of visible light is some 10,000 times larger than the typical distance between two atoms, we could not see individual atoms.