Tag archives: quantum theory

Einstein world record, Spider-Man physics, quantum films and cakes

By Sarah Tesh and James Dacey

A world-record-breaking hoard of Albert Einsteins invaded Toronto in Canada on Tuesday 28 March. 404 people gathered in the city’s MaRS Discovery District dressed in the genius’s quintessential blazer and tie, and sporting bushy white wigs and fluffy mustaches. As well as breaking the previous Guinness World Record of 99 Einsteins, the gathering kicked off this year’s Next Einstein Competition. The online contest invites the public to submit ideas that can make the world a better place and awards the winner $10,000 to help them realize it.

View all posts by this author | View this author's profile

Quantum punchlines, the cloud atlas, NASA schooled

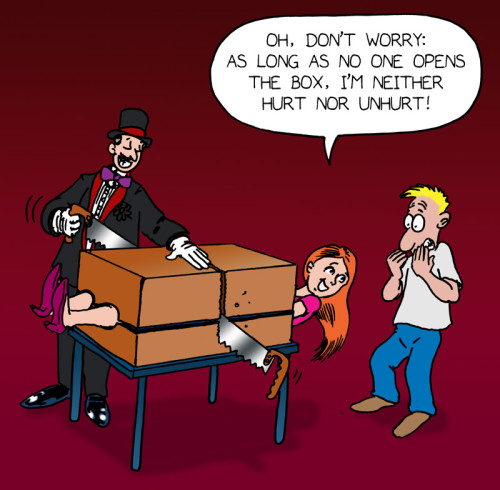

Quantum humour: is the joke dead or alive? (Creative Commons/Benoît Leblanc)

By Sarah Tesh

You may not normally associate humour with quantum theory, but it’s not just jokes about Schrödinger’s cat and Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle that links the two. Liane Gabora of the University of British Columbia in Canada and Kirsty Kitto of Queensland University of Technology in Australia have created a new model for humour based upon the mathematical frameworks of quantum theory. The idea for their “Quantum Theory of Humour” stems from jokes like “Time flies like an arrow. Fruit flies like a banana.” Separately, the statements aren’t amusing but together they make a punchline. This requires you to hold two ideas in your head at once – a concept analogous to quantum superposition.

Using pottery to communicate science

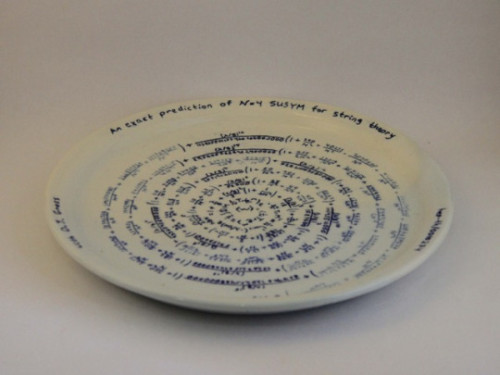

Showcasing science – one of the ceramic items created by Nadav Drukker on show at the new Quantum Ceramics exhibition in London. (Courtesy: Nadav Drukker)

By Matin Durrani

You might not think theoretical physics and pottery have much in common. But they do now, thanks to a new exhibition being staged at the Knight Webb Gallery in Brixton, south-east London, which opens today.

Entitled Quantum Ceramics, the exhibition is the first solo display of ceramic works by theoretical physicist Nadav Drukker. Based at King’s College London, Drukker makes traditional studio pottery as a new way to communicate his scientific research.

Drukker, who is a string theorist, has six different projects – entitled “Circle”, “Cusp”, “Index”, “Polygons”, “Cut” and “Defect” – with each inspired by one of his research papers. His works are all traditional glazed stoneware and porcelain vessels, but decorated with mathematical symbols.

View all posts by this author | View this author's profile

Happy New Year! The January 2017 issue of Physics World is now out

By Matin Durrani

By Matin Durrani

Happy New Year from all the team at Physics World!

To get things off to a cracking start, check out the January issue of Physics World magazine, which has a wonderful feature by Patrick Hayden and Robert Myers about how the study of “qubits” – quantum bits of information – could be key to uniting quantum theory and general relativity. The issue is now live in the Physics World app for mobile and desktop, and you can also read the article on physicsworld.com from tomorrow.

Elsewhere in the new issue, you can discover how physicists have waded into the debate over whether magnetic fields can control neurons and enjoy a great feature on why some birds don’t kick out intruder cuckoo eggs.

You can also find out just why so many physicists are worried about Donald Trump’s imminent inauguration as US president.

View all posts by this author | View this author's profile

‘Anomalous weak values’ are nonclassical, and here is the proof

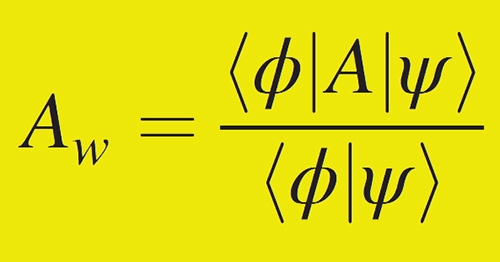

The weak value of an observable A can be nonsensical.

By Hamish Johnston

Last month we reported on a quirky paper in Physical Review Letters entitled “How the result of a single coin toss can turn out to be 100 heads” by Christopher Ferrie of the University of New Mexico and Joshua Combes of the Perimeter Institute for Theoretical Physics in Waterloo, Canada.

The paper addresses “anomalous weak values” in quantum mechanics, a phenomenon that was first identified in 1988 by Yakir Aharonov, Lev Vaidman and colleagues at Tel Aviv University. A weak value is the result of a weak measurement on a quantum system. This is done by making repeated gentle measurements on the quantum states of identical particles. The result of each measurement only has a tiny correlation to the quantum state of the particle so the wave function of the particle does not collapse into that state. However, by making the measurement on many particles, a weak value providing useful information about the state can be obtained.

View all posts by this author | View this author's profile

Celebrating the life and work of John Bell

By Matin Durrani

This year marks the 50th anniversary of the publication of a now-famous paper in the journal Physics by the Northern Irish physicist John Bell, in which he proved that making a measurement on one particle could instantaneously affect another particle – even if it’s a long way off.

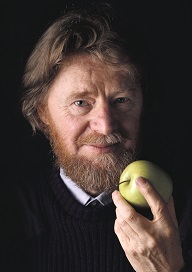

Food for thought: John Bell’s theorem is 50 years old. (Courtesy: Peter Menzer)

As our regular columnist Robert P Crease writes in the November issue of Physics World magazine, that kind of instantaneous effect, which proved the concept of entanglement, was not something that Bell was originally keen on. In fact, Bell had actually set out to prove the opposite – that it was possible, using “hidden variables”, to have a theory of physics that could keep things nice and “local”, and so avoid what Einstein had dubbed “spooky action at a distance”.

But Bell reversed his thinking. “I made a phase transition in my mind,” he told Crease shortly before his death in 1990 aged 62.

Yesterday (4 November) marked the 50th anniversary of the day that Bell’s paper arrived at the journal’s offices and today (5 November) sees the opening of an exhibtion at the Naughton Gallery on the campus of Queen’s University Belfast, from which Bell graduated with a first-class degree in mathematical physics in 1949.

Entitled “Action at a distance”, the exhibition runs until 30 November and promises to “explore Bell’s life and the artistic response to his legacy by artists from across the world”. There is also an accompanying series of lectures from Andrew Whitaker, Maire O’Neill, Mauro Paternostro, Artur Ekert and Anton Zeilinger.

View all posts by this author | View this author's profile

Fine-tuning quantum features to develop future technologies

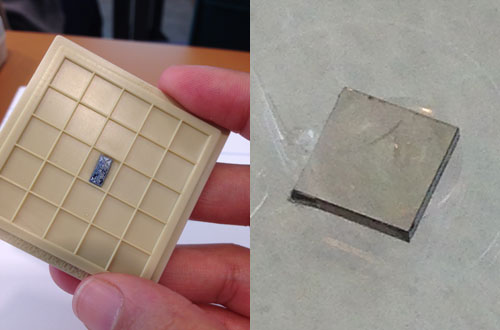

Quantum kit: two superconducting qubits (left) and an artificial diamond with an NV centre (right). (Courtesy: Tushna Commissariat)

By Tushna Commissariat

I’ve left sunny Stockholm and I’m back at the office in blustery Bristol, but I still have a few good quantum tales to tell from the science-writers’ workshop at NORDITA last week. On Thursday, the main speaker of the day was Raymond Laflamme, who is the current director of the Institute for Quantum Computing at the University of Waterloo in Canada. Laflamme – who kick-started his career working on cosmology at the University of Cambridge in the UK as a student of Stephen Hawking – studies quantum decoherence and how to protect quantum systems from it by applying quantum error-correction codes, as well as using nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) to develop a scalable method of controlling quantum systems.

View all posts by this author | View this author's profile

What can you learn at a quantum ‘boot camp’?

By Tushna Commissariat in Stockholm, Sweden

Google the word “quantum” and take a look at what comes up.

In addition to the obvious news articles about the latest developments in the field and the Wikipedia entries on quantum mechanics, you’ll undoubtedly come across a heap of other, seemingly random, stories.

I found, for example, a David Bowie song being compared to a quantum wavefunction (by none other than British science popularizer Brian Cox), as well as a new cruise ship being named Quantum of the Seas. Then there’s the usual jumble of pseudo-scientific “wellness” therapies that misguidedly adopt the word in a strange attempt to give their treatments some sort of credibility.

So while it seems that everyone is talking about quantum something or other, how much do we really understand this notoriously difficult subject? More to the point, how much do science journalists, like me, really know about the subject? I write stories about quantum mechanics from time to time for Physics World and the subject can, I assure you, be fiendish and quite mind-bending.

Entering the quantum world

Not a black hole in sight: Raymond Laflamme in one of the IQC labs. The machine behind him makes diamonds for quantum-computing experiments.

By Hamish Johnston in Canada’s Quantum Valley

“We have entered the quantum world and we can control it” is how Raymond Laflamme characterizes the current quantum renaissance that is sweeping across many fields of physics. Laflamme is director of the Institute for Quantum Computing (IQC) at Canada’s University of Waterloo and he began his career at the University of Cambridge as a student of Stephen Hawking, working on cosmology.

A ‘unique’ quantum research centre

Vadim Makarov with a few old friends.

By Hamish Johnston in Canada’s Quantum Valley

“There’s no place like this in the world,” said Vadim Makarov (above) as we walked up to his lab at the Institute for Quantum Computing (IQC) at Canada’s University of Waterloo. What’s unique about the place, according to Makarov and others I spoke to in Waterloo, is that it brings together a diverse group of researchers (physicists, computer scientists, mathematicians, engineers, etc) in one place to develop quantum-information technology.