Tag archives: cosmology

See in the new year with the January 2018 issue of Physics World

Happy new year and welcome back to Physics World after our winter break. Why not get 2018 off to a great start with the January 2018 issue of Physics World, which is now out in print and digital format.

In our fantastic cover feature this month, Imre Bartos from Columbia University in New York examines the massive impact on physics that last year’s spectacular observation of colliding neutron stars will have.

Elsewhere, Bruce Drinkwater from the University of Bristol explains how he is using ultrasonics to monitor the damaged Fukushima nuclear-power plant in Japan, while science writer Jon Cartwright looks at how technology can help blind physicists.

Don’t miss either our interview with Fermilab boss Nigel Lockyer and do check out our tips for how to brush up your CV if you’re chasing a job in industry.

View all posts by this author | View this author's profile

Test your brains with the Physics World blackboard quiz

By Matin Durrani

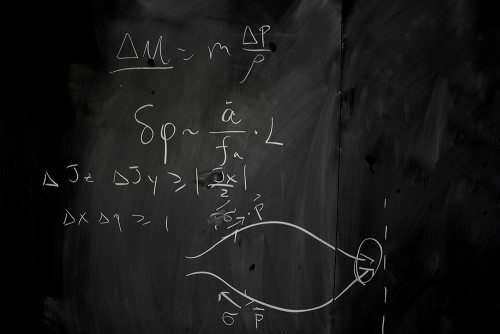

Can you tell what branch of physics is being described on the blackboard above? It’s one of six photographs taken by the communications folks at the Perimeter Institute for Theoretical Physics in Waterloo, Canada, where blackboards are an integral feature of the building’s design, appearing everywhere from the lifts to coffee areas.

In this quiz, your task is to study six blackboards and match them up with the physics topics they represent. There’s no prize, other than the satisfaction of having at least some inkling of what those clever theorists at the Perimeter are up to.

So here are the six topics:

• Accretion physics and general relativity

• Cosmology

• Neural networks and condensed matter

• Particle physics 1

• Particle physics 2

• Strings

And here are the six blackboards (you can click on each to see it in more detail).

The May 2017 issue of Physics World is now out

By Matin Durrani

By Matin Durrani

Einstein’s equations of general relativity might fit on a physicist’s coffee mug, but solving them is no mean feat. Now, however, the equations have been solved in a cosmological setting for the first time, as Tom Giblin, James Mertens and Glenn Starkman explain in the May 2017 issue of Physics World magazine, which is now live in the Physics World app for mobile and desktop

Elsewhere in the issue, you can enjoy an interview with John Holdren, who spent eight years as Barack Obama’s presidential science adviser. Find out too about the good and bad of nanoparticles and explore the potential that skyrmions – magnetic quasiparticles – could hold as a new form of memory storage.

Don’t miss either this month’s Lateral Thoughts, in which physicist Roger Todd describes how his invention of a system for automatically watering his house plants almost led to a commercial device.

Remember that if you are a member of the Institute of Physics, you can read Physics World magazine every month via our digital apps for iOS, Android and Web browsers.

View all posts by this author | View this author's profile

So you want to know about the dark universe?

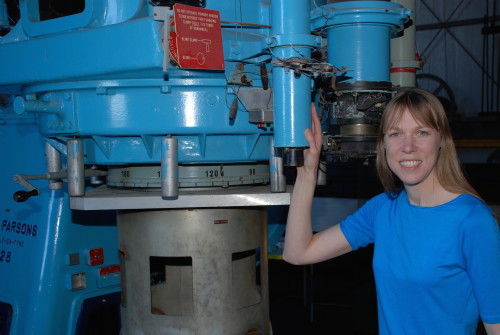

Big thinker – Catherine Heymans is an observational cosmologist at the University of Edinburgh and author of the new Physics World Discovery ebook The Dark Universe.

By Matin Durrani

It never ceases to amaze me that we know almost nothing about 95% of the universe. Sure, the consensus is that 25% is dark matter and the rest is something dubbed “dark energy”, but beyond that our knowledge is wafer thin.

The flip side, though, is that there’s plenty for physicists to get stuck into. And if you want to get up to speed with the field and find out more about some of its challenges, do check out a new free-to-read Physics World Discovery ebook by Catherine Heymans from the Royal Observatory, University of Edinburgh, UK.

Available in ePub, Kindle and PDF formats, The Dark Universe explains the dark enigma and examines “the cosmologist’s toolkit of observations and techniques that allow us to confront different theories on the dark universe”. And to get you in the mood for all things dark, I asked Heymans some questions about her life as a research scientist. Here’s what she had to say.

View all posts by this author | View this author's profile

The Science of Heaven

By Richard de Grijs in Beijing

Good things come to those who wait. Indeed, it has been almost six years since we initially thought about making an astronomy documentary set in China – and we finally showed it in public last month. The Science of Heaven premiered on 30 November 2016 at my institution, the Kavli Institute for Astronomy and Astrophysics at Peking University. By all accounts, it was very well received. While we are ironing out some final issues before releasing it publicly in early 2017, you can watch the trailer (above).

View all posts by this author | View this author's profile

Second wave: all about LIGO, black holes, gravitational ripples and more

By Tushna Commissariat

What an exciting week it has been, as the LIGO and Virgo collaborations announced that they have definitely detected a second gravitational wave event using the Advanced Laser Interferometer Gravitational-wave Observatory (aLIGO) in the US. These waves made their way into aLIGO early on Boxing Day last year (in fact it was still very late on Christmas Day in the US states where the twin detectors are located), a mere three months after the first gravitational-wave event was detected on 14 September 2015.

This event once again involved the collision and merger of two stellar-mass black holes, and since the “Boxing Day binary” is still on my mind, this week’s Red Folder is a collection of all the lovely images, videos, infographics and learning tools that have emerged since Wednesday.

LIGO physicist and comic artist Nutsinee Kijbunchoo has drawn a cartoon showing that while the researchers were excited about the swift second wave, they were a bit spoilt by the first, which was loud and clear – and could be seen by naked eye in the data. The black holes involved in the latest wave were smaller and a bit further away, meaning the signal was fainter, but actually lasted for longer in the detectors.

View all posts by this author | View this author's profile

Climate change and chaos, the many faces of physics, spider-silk superlenses and more

By Tushna Commissariat

In case you have ever wondered why so many theoretical physicists study climate change, physicist Tim Palmer from the University of Oxford in the UK has a simple answer: “because climate change is a problem in theoretical physics”. Indeed, Palmer, who won the Institute of Physics’ 2014 Dirac medal, studies the predictability and dynamics of weather and climate, in the hopes of developing accurate predictions of long-term climate change. The answer, according to Palmer, lies at the intersection between chaos theory and inexact computing – which requires us to stop thinking of computers as deterministic calculating machines and to instead “embrace inexactness” in computing. Palmer talked about all this and more in the latest public lecture from the Perimeter Institute in Canada – you can watch his full talk above.

When someone says the word “physicist”, what image or persona comes to mind? That is the question the Institute of Physics (which publishes Physics World) was hoping to answer with its recent member survey based on diversity, titled “What Does a Physicist Look Like?” The Institute’s main aim with this diversity survey, which about 13% of its members responded to, was “to understand the profile of our members and gain some insights into who they are – diverse people with different ages, ethnicities, beliefs and much more”. You can read its entire results here.

Getting a fix on quantum computations

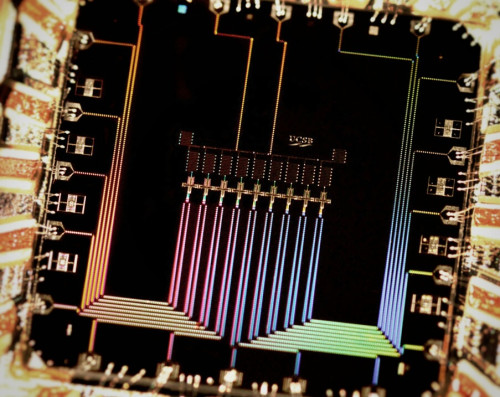

Bit of choice: A photograph of the nine superconducting qubit device developed by the Martinis group at the University of California, Santa Barbara, where, for the first time, the qubits are able to detect and effectively protect each other from bit errors. (Courtesy: Julian Kelly/Martinis group)

By Tushna Commissariat in New York City, US

Although the APS March meeting finished last Friday and I am now in New York visiting a few more labs and physicists in the city (more on that later), I am still playing catch-up, thanks to the vast number of interesting talks at the conference. One of the most interesting sessions of last week, and a pretty popular one at that, was based on “20 years of quantum error correction” and I went along to the opening talk by physicist John Preskill of the California Institute of Technology. I had the chance to catch up with Preskill after his talk and we discussed just why he thinks that we are not too far away from a true quantum revolution.

Just in case you haven’t come across the subject already, quantum error correction is the science of protecting quantum information (or qubits) from errors that would occur as the information is influenced by the environment and other sorts of quantum noise, causing it to “decohere” and lose its quantum state. Although it may seem premature that scientists have been working on this problem for nearly two decades when an actual quantum computer has yet to be built, we know that we must account for such errors if our quantum computers are ever to succeed. It will be essential if we want to achieve fault-tolerant quantum computation that can deal with all sorts of noise within the system, as well as faults in the hardware (such as a faulty gate) or even a measurement.

Over the past 20 years, theoretical work in the field has made scientists confident that quantum computing of the future will be scalable. Preskill says that “it’s exciting because the experimentalists are taking it quite seriously now”, while initially the interest was mainly theoretical. Previously, scientists would artificially create the noise in the quantum systems that they would correct but now actual quantum computations can be fixed. Indeed, Preskill says that one of the key things that has really moved quantum error correction along in the past few years is the concentrated improvement of the hardware used, i.e. better gates with multiple qubits being processed simultaneously.

The January 2016 issue of Physics World is now out

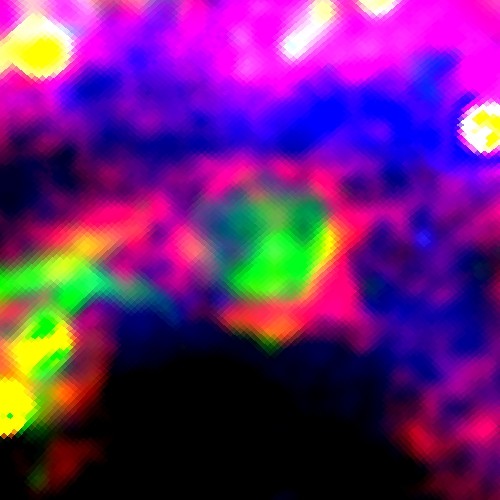

Polarized patterns: the cosmic microwave background as you’ve never seen it before. (Courtesy: Planck Collaboration)

By Matin Durrani

Happy new year and welcome back to Physics World after the Christmas break.

It’s always great to get a new year off to good start, so why not tuck into the first issue of Physics World magazine of 2016, which is now out online and through the Physics World app.

Our cover feature this month lets you find out all about the Planck mission’s new map of the cosmic microwave background. Written by members of the Planck collaboration, the feature explains how it provides information on not just the intensity of the radiation, but also by how much – and in which direction – it’s polarized.

View all posts by this author | View this author's profile

The life and times of Einstein – ‘A vagabond and a wanderer’

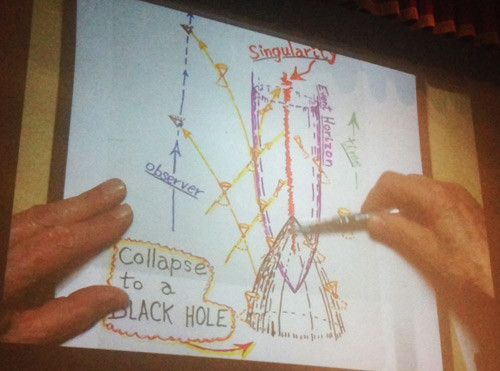

Falling in: Sir Roger Penrose’s sketch of a black-hole collapse. (Courtesy: Tushna Commissariat)

By Tushna Commissariat

So much has been said about Einstein and his general theory of relativity (GR) that one would assume there isn’t two entire days worth of talks and lectures that could shed new light on both the man and his work. But that is precisely what happened last weekend at Queen Mary University London’s “Einstein’s Legacy: Celebrating 100 years of General Relativity” conference, where a mix of scientists, writers and journalists talked about everything from the “physiology of GR” to light cones and black holes, to M-theory and even GR’s “sociological spin-offs”.

The opening talk, “Not so sudden genius”, was given by journalist and author of “Einstein: A hundred years of relativity“, Andrew Robinson. The talk was very fascinating and early on Robinson outlined that Einstein stood on the shoulders of many scientists and not just “giants” such as Newton and Mach. But he also acknowledged that the scientist was always a bit of a loner and he preferred it this way. Robinson rightly pointed out that until 1907, Einstein was “working in brilliant obscurity” and later, even once fame found him, rootlessness really suited Einstein’s personality – he described himself as “a vagabond and a wanderer”.