Tag archives: physics education

Physics graduate is just 14, high drama at the LHC, the physics of number two

By Hamish Johnston and Michael Banks

Carson Huey-You was just 11 years old when he arrived at Texas Christian University to study physics. Now, at the ripe old age of 14, he is about to graduate, according to an article in the Huffington Post. “I knew I wanted to do physics when I was in high school, but then quantum physics was the one that stood out to me, because it was abstract,” says Huey-You. Most American children start high school at age 14, but Huey-You was learning calculus by the time he was three – a subject usually reserved for high school seniors. And precociousness runs in the family because his younger brother Cannan is starting university in September aged 11. The siblings are delightful and interviewed in the above video.

View all posts by this author | View this author's profile

The most expensive object on Earth, publish or perish, and a physics Magna Carta

Gold coast: the Hinkley Point C power station will be built next to existing reactors in Somerset. (CC BY-SA 2.0 Richard Baker)

By Hamish Johnston

What will soon be the most expensive object on Earth? The answer, according to Greenpeace, is the Hinkley Point C nuclear power station that is slated for construction in south-west England. According to the BBC, the environmental group reckons the station will cost £24bn ($35bn) whereas EDF – the company that will build it – puts the construction cost at £18bn. In contrast, the Large Hadron Collider at CERN cost a mere £4bn. While the price tag on Hinkley Point C – which should produce 3.2 GW of electricity by 2024 – is eye watering, building a reactor on the cheap is not really an option.

Still, Hinkley Point C will not be the most expensive object ever built by humans. That honour goes to the International Space Station, which the BBC says cost nearly £78bn. There’s something comforting in knowing that the single highest expenditure ever has been on science – maybe civilization isn’t doomed after all.

Balloon-borne experiment will reveal how cosmic rays damage computer memories

By Tamela Maciel at the APS April Meeting in Baltimore, Maryland

Little bits: the CRIBFLEX logo. (Courtesy: Drexel University Society of Physics Students)

A group of undergraduate students at Drexel University in Philadelphia is ready to click “confirm” on an Amazon order that will include a weather balloon, a memory storage device, a GPS, a Geiger counter and a BeagleBoard computer (described to me as a “beefier version of Raspberry Pi”). For less than $2000, this team of physics, engineering and computer-science students plans to launch a weather-balloon experiment that will measure the effects of cosmic rays on DRAM memory devices at high altitudes.

The team is part of the Drexel University Society of Physics Students and the members presented their experiment design at the April Meeting of the American Physical Society in Baltimore, Maryland, last weekend.

DRAM is a very quick and simple type of electronic memory – each bit takes the form of a capacitor that either has charge or doesn’t, according to whether it’s storing a zero or one. Unfortunately, this simple design can make the bits very sensitive to radioactivity or cosmic rays, which can cause bits to flip values and introduce “soft errors” into the data.

What can you learn from Descartes?

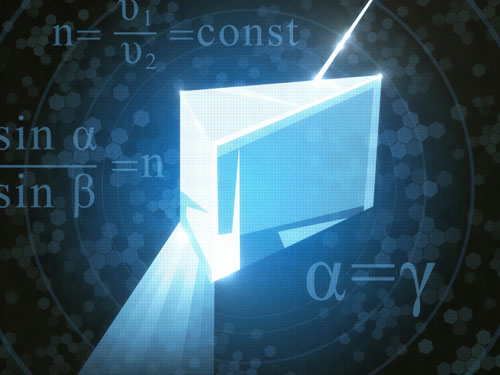

Taking Descartes back into the physics classroom. (Courtesy: Shutterstock)

By James Dacey in Córdoba, Argentina

What’s the best way to teach tricky physics concepts to students? Naturally, this was one of the questions underpinning many of the talks here at the International Conference of Physics Education (IPCE) in Córdoba. According to a couple of educationalists in Latin America at least, it seems that one approach is to enlist the help of some of the great scientists and philosophers of the past.

Patricia del V. Repossi, a lecturer at the Pontificia Universidad Católica Argentina in Buenos Aires, spoke about how she uses the history of science as a framework for teaching optics. Repossi explained how she had come to realize that some of the students taking her conventional optics course believed that photons are made of the same stuff as “tennis balls”. So, she and her colleagues set about transforming the way they teach the topic – by combining a physics class with a history lesson.

Thinking about thinking

Shining a light on teaching physics. (Courtesy: iStockphoto/Greyfebruary)

By James Dacey in Córdoba, Argentina

There has been a lot of fancy language flying around here at the International Conference on Physics Education (ICPE), which is taking place in Córdoba. Words such as “pedagogy” and “metacognition” roll off the tongues of education researchers as naturally as a particle physicist at CERN saying the words “Higgs boson”.

At first it seemed a bit like a foreign language to me, but I’ve started to realize that one of the recurring ideas at the conference can be described in more everyday terms: thinking about thinking. Teachers should think about the way they think about learning, and the way their students think about learning.

View all posts by this author | View this author's profile

Turning a physics class into a video game

Could computer games like Rock of Ages, which can be played by several people at once using split screens, help inspire better physics courses? (CC BY-SA Rock of Ages by ACE Team)

By James Dacey in Córdoba, Argentina

“When was the last time you heard a student say they wanted a physics course that was long and difficult?”

That was a rhetorical question that physicist and education researcher Ian Beatty put to us today while delivering his keynote talk at the International Conference on Physics Education (ICPE) 2014 here in Argentina. Beatty’s point is that two of the worst things that people say about computer games is that they are too easy or that they end too quickly. Needless to say, he had never heard such protestations from his physics students!

Beatty, a physicist and educational researcher at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro in the US, believes that course creators could learn a trick or two from game designers. He has therefore spent the past three years trying to understand what it is about video games that makes them so appealing to gamers, and how to incorporate some of the underlying principles into a physics course.

Physics education under the microscope in Argentina

A warm welcome from Argentina.

By James Dacey in Córdoba, Argentina

I’m writing this blog entry from the heart of Argentina, following a marathon 30-hour journey from my home in Bristol, UK. It was a trip that included two planes, a few buses, a couple of taxis and several long walks, but I’m finally here in Córdoba – Argentina’s second largest city – to attend this year’s International Conference on Physics Education (ICPE).

The meeting’s all about bringing together people to discuss the latest developments in education – including lecturers, teachers, trainers, students and educational researchers. It’s an event with a global outlook, accompanied by a satellite meeting where local high-school teachers will be discussing issues more focused on their day-to-day experiences. At the registration session, things already took a welcome Argentine twist as we were treated to a performance from some local musicians (see picture above).

View all posts by this author | View this author's profile

Hello Kitty in space, Lord of the Rings physics homework and more

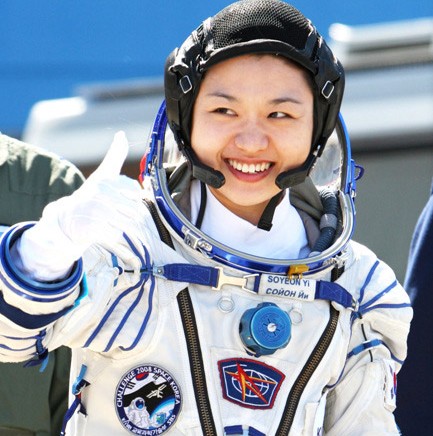

Yi on the day of her launch – 8 April 2008. (Courtesy: NASA)

By Tushna Commissariat

This week, South Korea’s one and only astronaut, 36-year-old Yi So-yeon, has quit her job, thereby signalling the end of the country’s manned space programme for the time being. In 2008 Yi became the first Korean to go into space, when for 11 days she travelled on board a Russian Soyuz spacecraft to the International Space Station, after being chosen through the government-run Korean Astronaut Program. Yi cited personal reasons for quitting, but has been studying for an MBA in the US since 2012. You can read more about her work and reasons for leaving in articles from Australia Network News and abc News.

Choosing physics, or not

By Margaret Harris

I’ve been mulling over this topic for a while, but a pair of blog posts this week has finally prompted me to write about it. One of them, entitled “Why I won’t be studying physics at A-level” appeared yesterday in the education section of the Guardian newspaper. In it, the anonymous female author lists a number of reasons why she is leaving physics, including a lack of female teachers and an “uninspiring” GCSE physics syllabus that “seemed out of touch compared with the stem cells and glucoregulation we were studying in biology”. There’s plenty to debate there already, but to me, the following paragraph was the most striking:

“I don’t dislike physics; neither do I find it boring or particularly difficult. But I do enjoy my other subjects more, so when it came to choosing between physics and geography for my fourth AS-level I opted for the latter. I thought it would be good to take a humanities subject to balance out the sciences.”

Physics in the fast lane

By Matin Durrani

Most of us want everything in life right here, right now. From fast food to fast cars, none of us can be bothered to hang about any longer than absolutely necessary. Where’s your reply to my e-mail I sent five minutes ago? Why haven’t you responded to my Tweet? Do you really expect me to read that 500-page novel for fun?

It was perhaps as an antidote to the ever-faster pace of life that so much has been made of two physics experiments that recently produced new data for the first time in years. I’m talking, of course, about the “pitch-drop” experiments at Trinity College Dublin in Ireland and the University of Queensland, Australia, which both consist of a glass funnel of sticky tar-like substance. A drop from the Trinity experiment finally fell last July, with a video of the event quickly going viral, while the Queensland set-up dripped this April for the first time in 13 years. (For more on why both experiments proved so popular, check out our great feature by Shane D Bergin, Stefan Hutzler and Denis Weaire from Trinity.)

But if you can’t be bothered to hang around for 10 years or more, you’ll be pleased to hear that physicists at Queen Mary University of London – led by Kostya Trachenko – have now set up a new pitch-drop experiment to explore the difference between solid and liquids on the much shorter timescale of just a few months.

View all posts by this author | View this author's profile