Tag archives: careers

Got your physics degree… now what?

Last year, we launched our first ever Physics World Careers guide, which brought together all of our best content from the careers section of our monthly magazine, together with an extensive directory of employers. This year, we’re back with the bigger Physics World Careers guide 2018, packed with case-studies and analyses, to help you choose the right path for your future – as James McKenzie, vice-president for business at Institute of Physics point out in his foreword for the guide, “As physicists, you will have learnt to be logical, analytical and articulate. These are skills that are highly prized by employers and open up many career paths for you.”

View all posts by this author | View this author's profile

The physics of bread, the quest for metallic hydrogen and adventures in LIGO land

By Matin Durrani

By Matin Durrani

If you’re a student wondering whether to go into research or bag a job in industry, don’t miss our latest Graduate Careers special, which you can read in the October issue of Physics World.

Philip Judge from the US National Center for Atmospheric Research and his colleagues Isabel Lipartito and Robert Casini first describe how budding researchers should pick a PhD to work on. It’s vital as that first project can determine the trajectory of your future career.

But if your eyes are set on a job outside academia, careers guru Crystal Bailey from the American Physical Society runs through your options and calls on academics to learn more about what’s on offer so they can advise their students better.

If you’d rather just stick your head in the sand about your career options, however, then why not enjoy the cover feature of the October issue, in which former Microsoft chief tech officer and Intellectual Ventures boss Nathan Myhrvold discusses his massive new five-volume treatise Modernist Bread.

Mixing history and science – as well as the results of more than 1600 of his own experiments – the book is sure to be the last word on this foodstuff that humans have been baking for millennia.

Don’t miss either Jon Cartwright’s feature on the quest for metallic hydrogen.

Remember that if you’re a member of the Institute of Physics, you can read the whole of Physics World magazine every month via our digital apps for iOS, Android and Web browsers.

View all posts by this author | View this author's profile

Visiting the most powerful laser in the world

By James Dacey

You might find this surprising, but Romania is one of the main reasons I became a journalist. Back in 2006, having recently graduated with a degree in natural sciences, I spent the summer in the Transylvanian city of Brasov, teaching English to school kids. While there, I was talked into writing a few articles about my experiences for the local tourism magazine, Brasov Visitor. To cut a rambling story short, I had a memorable summer and caught the writing bug. Eventually, I landed a job at Physics World, which enabled me to combine my journalistic leanings with my scientific background.

View all posts by this author | View this author's profile

Your future with physics

By Margaret Harris

By Margaret Harris

In a typical month, the careers section of Physics World features the stories of two different physicists: one who is working in a physics-related field (such as engineering or teaching), and another who decided to do something totally different (such as designing sailboats or running a winery).

I find these stories endlessly fascinating, and when I was Physics World’s careers editor, I loved sharing them with the wider physics community. But the section isn’t there just to add human interest. It’s also giving current students (and later-career physicists seeking a change) a better idea of what they could do with their physics knowledge in the workplace.

After talking to students and careers professionals, I realized that publishing two stories in the magazine once a month wasn’t really the ideal way of doing this – at least, not for readers who are actively looking for careers ideas, and who might therefore prefer to learn about lots of different options at once.

So with these readers in mind, we’ve come up with a brand-new publication for 2017. The first edition of Physics World Careers contains a selection of the best articles published in the magazine’s careers section last year, plus an extensive employer directory.

View all posts by this author | View this author's profile

LGBT engineers share their inspiring experiences

By James Dacey

February in the UK is LGBT History Month, an annual event to promote equality and diversity for the benefit of the public. This year, three engineering organizations have got involved by producing a series of online videos profiling lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) engineers. According to the Royal Academy of Engineering, InterEngineering and the engineering firm Mott MacDonald, the ‘What’s it Like?’ video series is designed to “inspire prospective engineers who are LGBT, as well as existing engineers who may wish to come out or transition at work”.

The video above features a medley of quotes from people profiled in the films, including Mark McBride-Wright, who is the chair and co-founder of InterEngineering and a gay man. A not-for-profit outfit, InterEngineering seeks a more inclusive profession by running panel discussions and providing career development opportunities for LGBT engineers. “As a profession, we are at the beginning of a journey creating an inclusive industry for everyone and I hope these videos will play a part in attracting LGBT+ students to the engineering industry,” says McBride-Wright.

View all posts by this author | View this author's profile

From physics degree to Hollywood

By James Dacey

This summer many of you will watch smoke billowing out of buildings as yet another villain wreaks havoc on the New York skyline in the latest Hollywood blockbuster. I’m willing to bet that as you eat your popcorn you won’t be thinking about the Navier–Stokes equations of fluid dynamics. (Well, perhaps you will now that I’ve mentioned it!)

In fact, part of the reason that virtual smoke in films looks so realistic is because visual effects (VFX) specialists have applied the Navier–Stokes equations to their graphics. This was one of the interesting tidbits I learned from a talk yesterday in London by Rob Pieké, head of software at Moving Picture Company (MPC).

Pieké was speaking as part of a half-day event on “physics and film” organized by the Institute of Physics, which publishes Physics World. The gist of his presentation was that basic physics principles are used in a variety of ways to create special effects that capture viewers’ attention. “The audience wants to see something fantastical but grounded in reality,” said Pieké. Another example he gave was how naturally bouncing hair in computer-generated characters is modelled on mass—spring systems. Each individual hair could be modelled on as many as 30 masses connecting by springs.

View all posts by this author | View this author's profile

China eyes new high-energy collider

Matin Durrani outside the Institute of High Energy Physics in Beijing before interviewing Xinchou Lou.

By Matin Durrani in Beijing, China

I had just landed in Beijing this morning when I saw an e-mail from my colleague Mingfang Lu waiting for me on my phone. Mingfang, who’s editor-in-chief at the Beijing office of the Institute of Physics, which publishes Physics World, has been helping me to organize my itinerary for the next week as I gather material for our upcoming special report on physics in China. You may remember we published a Physics World special report on China in 2011 but so much has happened since then that we felt it’s easily time for another.

Mingfang’s e-mail was to say we would be off at 2.30 p.m. to interview Xinchou Lou, a particle physicist at the Institute of High Energy Physics, about the country’s ambitious plans for a “Higgs factory”. If built, this 240 GeV Circular Electron–Positron Collider (CEPC) would be a huge facility (50 km or possibly even 100 km in circumference) that will let physicists study the properties of the Higgs boson in detail. I say “if”, but knowing China’s frenetic progress in physics, it will almost certainly be a case of “when”.

View all posts by this author | View this author's profile

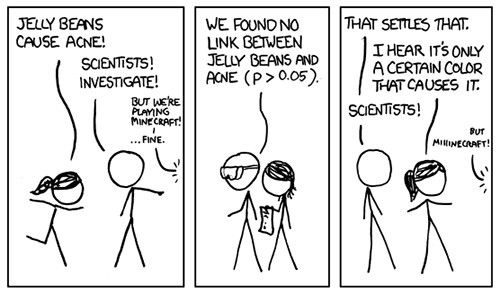

On the frontline of the ‘reproducibility crisis’

By Margaret Harris

The “reproducibility crisis” in science has become big news lately, with more and more seemingly trustworthy findings proving difficult or impossible to reproduce. Indeed, a recent Nature survey found that two-thirds of respondents think current levels of reproducibility constitute a “major problem” for science. So far, physics hasn’t been affected much; the crisis has been most severe in fields such as psychology and clinical research, which, not coincidentally, involve messy human beings rather than nice clean atomic systems. However, that doesn’t mean it’s irrelevant to physicists. Last month, I had the pleasure of speaking to three physics graduates who have become personally involved in addressing the reproducibility crisis within their chosen profession: medicine.

Henry Drysdale, Ioan Milosevic and Eirion Slade are third-year medical students at the University of Oxford. All three earned their undergraduate degrees in physics, and they now make up one-third of COMPare – an initiative by Oxford’s Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine (CEBM) that tracks “outcome switching” in clinical trials. As Drysdale explained to me over coffee in an Oxford café, researchers who want to perform clinical trials have to state beforehand which “outcomes” they intend to measure. For example, if they are trialling a new drug to treat high blood pressure, then “blood pressure after one year” might be their main outcome. But researchers generally keep track of other variables as well, and often their final report focuses on a positive result in one of these other parameters (a dip in the number of heart attacks, say), while downplaying or ignoring the drug’s effect on the main outcome.

View all posts by this author | View this author's profile

More data needed on the STEM ‘shortage’

(Courtesy: iStock/geopaul)

By Margaret Harris

“Science has always been the Cinderella amongst the subjects taught in schools…not for the first time our educational conscience has been stung by the thought that we are as a nation neglecting science.”

Sounds like something David Cameron or Barack Obama might have said last week, right? Wrong. In fact, it comes from a report by the grandly named Committee to Enquire into the Position of Natural Sciences in the Educational System of Great Britain, which presented its findings clear back in…1918.

I came across this quotation thanks to Emma Smith and Patrick White, a pair of education researchers at the University of Leicester who have spent the past few years studying the long-term career paths of people with degrees in science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM). Smith and White presented the preliminary findings of their study at a seminar in Leicester yesterday, and one of the themes of their presentation – reflected in the above quote – was the longevity of concerns about a shortage of STEM-trained people, especially university graduates. As Smith pointed out, worries about the number and quality of STEM graduates are not new and, historically, reports of a “STEM crisis” have been as much about politics as they have economic supply and demand.

View all posts by this author | View this author's profile

The STEM jobs paradox rumbles on

On balance: STEM shortages and surveys.

By Hamish Johnston and Margaret Harris

Are countries such as the UK, the US and Canada suffering from a shortage of scientists and engineers, or are scientists and engineers struggling to find jobs there? Our US correspondent Peter Gwynne reports that, according to a recent survey, physicists in that country can expect to be rewarded with handsome salaries if they work in industry – which suggests that their skills are in great demand. However, over in the New York Review of Books, an article on “The frenzy about high-tech talent” claims that “by 2022 the [US] economy will have 22,700 non-academic openings for physicists. Yet during the preceding decade 49,700 people will have graduated with physics degrees.”

In the past few years, Physics World has published several articles on the “STEM shortage paradox”, where reports of severe skills shortages in science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) coexist with lukewarm – and sometimes borderline alarming – data on employment in these fields. Hence, conflicting reports on career prospects for physicists don’t really surprise us anymore (although this is actually slightly different to what we’ve seen before, in that rosy employment data are going up against a downbeat statement about demand, rather than vice versa). But even so, when two reports point in such different directions, it’s tempting to conclude that one of them must be wrong, or at least missing something important.

View all posts by this author | View this author's profile